PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

GEORGE MCGOVERN'S $1,000 PROMISSORY NOTELoren Gatch wries: When Fred Reed was editor of Paper Money, he encouraged me to write about strange stuff like political satire notes, and Benny Bolin has been kind enough to keep indulging my interest in this topic. Forthcoming in Paper Money is the attached article, "George McGovern's $1,000 Promissory Note", about a common example of political scrip that appeared at the Republican National Convention in 1972. We are tweaking the relative size of the photographs and the notes, but the text will run as it is.   Here's an excerpt from the article. Thanks! -Editor

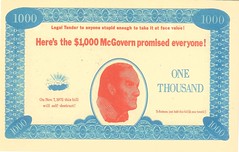

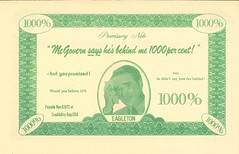

While the word “flip-flop” has been a part of America’s political lexicon since the early 20th century, as a piece of political invective the term has become widespread only in the last generation. As with most political speech, the more it has been used the less it means. Nowadays, almost any apparent inconsistency—or even the intellectually honest act of changing one’s mind—gets a public figure in hot water. Back in 1972, however, “flip-flop” did most definitely describe the behavior of the Democratic Party’s presidential candidate, George McGovern, towards his running mate, Thomas Eagleton. The fiasco of McGovern’s embrace and then disavowal of his vice-presidential choice not only created the “Eighteen-Day Running Mate” but gave rise to a widely-available example of political scrip, George McGovern’s $1000 Promissory Note. The convention proceedings in Miami Beach stretched on in a way that rushed the selection of McGovern’s vice-presidential candidate. When other alternatives, like Boston’s mayor Kevin White, proved unacceptable, the McGovern forces finally turned to Thomas Francis Eagleton (1929-2007), the junior senator from Missouri. While not as well-known as Kennedy, Eagleton’s Catholicism and his links to organized labor promised to balance the ticket in a similar way. With hardly any vetting of his background, Eagleton was offered a spot on the ticket on July 13 in a phone conversation with McGovern that lasted barely one minute. It was only after accepting the nomination that Eagleton confirmed rumors that since 1960 he had been hospitalized three times for depression, and twice undergone electroconvulsive—popularly called “electroshock”—therapy. Not only had Eagleton dissimulated in failing to tell the McGovern campaign about these episodes, he continued to resist explaining his medical record in any detail. Eagleton’s stance put the McGovern campaign in a terrible bind. Forcing Eagleton off the ticket would look callous, and destroy McGovern’s image as a different, and more principled, type of politician. Yet keeping Eagleton raised enormous doubts about the competence of a man who might be second in line to assume the presidency, as well as about McGovern’s own sense of judgment. In a joint press conference with McGovern on July 25, Eagleton first publicly confirmed his past hospitalizations, and McGovern famously declared that “I am 1,000 percent for Tom Eagleton and have no intention of dropping him from the ticket.” The statement was, according to Theodore H. White, “possibly the most damaging faux pas ever made by a Presidential candidate.” The pushback against McGovern’s decision was intense. The liberal press was against Eagleton; donations to the Democratic Party dried up; and McGovern’s own campaign workers were dealt a demoralizing blow. McGovern’s unfortunate use of the term “1,000 percent” regarding Eagleton also resonated with one of his earlier campaign proposals to reform the country’s welfare system. McGovern had proposed to give each American a $1,000 payment (a “demogrant”); an idea that, linked with a broader tax reform, actually had a certain academic pedigree and was a forerunner of what later emerged as the Earned Income Tax Credit. On its face, though, the notion was easy to caricature; Humphrey ridiculed it during the California primary, while Nixon’s campaign director Clark MacGregor called it a “$1,000-perperson giveaway program that would split America permanently into a welfare class and a working class.” A short time later, during the Republican convention (also in Miami Beach), Scripps- Howard newspapers noted how “funny money—fake $1,000 bills bearing the face of Democratic presidential nominee George S. McGovern—floods convention hotels.” Dispensed over souvenir store counters at the convention, the $1,000 bills sport a red profile of McGovern, facing to his left, framed by blue scrollwork. The text, also in red, reads “Here’s the $1,000 McGovern promised everyone”, “Legal tender to anyone stupid enough to take it at face value”, and with the promise that “On Nov. 7, 1972 this bill will self-destruct.” The reverse (of which there seem to be two varieties, one printed brown, and another green) is labeled a “promissory note” with a portrait of an agitated and perspiring Eagleton mopping his brow. “McGovern says he’s behind me 1,000 percent”, “but…he didn’t say how far behind!” This side is described as “Payable Nov. 8, 1972, at Credibility Gap, U.S.A.” Crudely printed on the cheapest paper, the parody notes deftly juxtaposed the two lines of attack directed at McGovern’s candidacy: that his policy proposals were too radical for the nation and that his treatment of Eagleton reflected poorly on McGovern’s character and judgment. Reproduced in facsimile in newspapers across the country, the notes themselves quickly showed up at political events as far away as San Antonio, Texas. The Democrats never recovered from the Eagleton debacle, and the McGovern-Shriver ticket went on to lose in November 1972 by the widest margin of the popular vote in the history of presidential elections. After the Eagleton experience, vice presidential nominees were never again selected so casually and without proper background checks.  Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|