PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

THE TINIEST ANCIENT COINSMike Markowitz published another nice article in his CoinWeek Ancient Coin

Series on October 20, 2014. My presentation of an excerpt here is pretty ham-handed. Be sure to see

the complete version online. Excellent graphics! -Editor

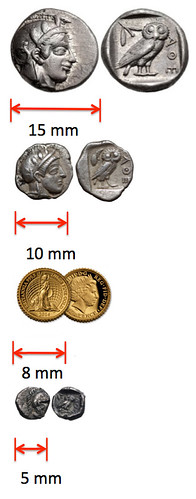

In 2014 the British Royal Mint issued a gold proof 50p coin only 8 mm in diameter*, weighing in at 1/40 Troy ounce (0.8 grams.) This is the smallest coin the UK has ever struck and surely one of the smallest modern coins. For comparison, the smallest coin the US Mint has ever produced–the US gold dollar, struck in several designs from 1849 to 1889–weighed 1.672 grams and measured 12.7 to 14.3 mm. Compared to the smallest coins of Antiquity, these little trinkets are big bruisers. In this article we will explore just how tiny coins can get. There are three ways a coin can be tiny: weight, dimension (diameter and thickness), and value. The Latin motto of the American Numismatic Society is Parva Ne Pereant: ”let not the small things perish.” The survival of so many extremely small coins from the remote past shows how appropriate this slogan is for people who treasure ancient coins. Metrology is the study of weights and measures. With relentlessly logical minds, but lacking the advantage of decimal notation, ancient Greeks created systems of weights based on simple fractions. These became the basis of their coinage denominations.   To find the tiniest ancients we have to go even further back in time, to the electrum coinage of Lydia and the Greek cities of Asia Minor. Like most questions in classical numismatics, the dating of these coins is controversial, but circa 650 BCE is the earliest guess for unmarked types and ca. 630-620 for types stamped with designs. The weight standard was based on a stater of about 14 grams, worth three month’s salary for a mercenary. Because electrum was so highly valued, most of the coins were smaller; thirds, sixths, twelfths, and twenty-fourths. The 1/24 stater, weighing about 0.57 grams and measuring only about 6 mm in diameter, could purchase a sheep or a bushel of grain (Linzalone). But the need for even smaller units in the day-to-day transactions of city life led to the production of miniscule 1/48 and 1/96 staters. At 3 or 4 mm in size, weighing just 0.15 to 0.10 grams, these are the smallest coins issued in the ancient world. I find it easier to avoid the decimals and just think of the weight as 150 to 100 milligrams. To keep this in perspective, an aspirin tablet weighs 325 milligrams.   By the fifth century, inflation had reduced the value of Roman copper small change to nearly nothing. The names of the denominations are often uncertain, so numismatists use a code based on the diameter of the coins. The smallest denomination is designated as AE4 and it was probably called a nummus, which simply means “coin”. In the local coinage of first century Judea, the smallest denomination was a bronze coin called a lepton in Greek and a half prutah in Hebrew. The smallest denomination coin known to the translators of the King James Version of the Bible (begun 1604, published 1611) was the Flemish mijt or “mite,” a debased silver piece of about 0.7 gram, worth half a farthing or 1/8 of a penny. It never circulated in England, but the word was familiar enough to contemporary readers that “mite” was used to translate lepton. The smallest coins are likely to have a low survival rate, which makes them relatively scarce. For most collectors, they lack the “eye appeal” of their larger cousins. They seldom appear in major auctions, and few dealers have many in stock, so they can be quite challenging to collect. The upside of this is that when they do appear on the market, they can be quite affordable. Well-worn, poorly struck examples of the bronze “Widow’s Mite,” commonly found in large numbers in the Holy Land, can often be purchase for under $20. To read the complete article, see:

Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|