PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

THE SAINT-GAUDENS CORNISH MASQUE PLAQUETTE

An article by Erik Goldstein in the September 2015 issue of The Numismatist discusses a rare medal created by one of

America's greatest sculptors and coin designers, Augustus Saint-Gaudens. Here's an excerpt; be sure to read the complete article.

The magazine is a benefit of membership in the American Numismatic Association. -Editor

Also found in “Gus” Saint-Gaudens’ portfolio of small works are a few medals produced either in miniscule numbers for friends or for monumental events like the 1889 centennial of George Washington’s presidential inauguration, the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition or Theodore Roosevelt’s 1905 inauguration. But Saint-Gaudens created one medal that has all but escaped the notice of mainstream American numismatics. Not only was it truly wrought by the great sculptor himself, but he also paid for the entire production and personally distributed examples to his good friends. Incredibly, he did this while his health and his life were slipping away and he was designing what would become our most beautiful circulating coins. Referred to as the “Cornish Masque plaquette,” the piece is fully understood only by looking beyond numismatics and seeing Saint-Gaudens as a sculptor, teacher and individual. Fed up with the New York rat race in the mid-1880s, the artist gradually moved his family and studio to an 18th-century estate in Cornish, New Hampshire, which he later purchased and dubbed “Aspet.” There he could work and enjoy life in the idyllic mountains of New England while escaping the steam and stench of summer in the city. But Gus was not the only person attracted to this bucolic setting: almost immediately, artistic friends of all disciplines and abilities began to arrive in and around Cornish. By the turn of the century, the Saint-Gaudenses, and a few others dubbed “Chick - a dees” (because they, like the small birds, were yearround residents), called the area home. Unwittingly, Augustus Saint-Gaudens and his wife, Augusta, started a phenomenon now recognized as a landmark in the history of American arts, casually referred to as the Cornish Art Colony. By the time the colony petered out after the First World War, some if its members included famous painters like Maxfield Parrish, Kenyon Cox and Thomas Dewing, along with numismatically familiar sculptors such as Paul Manship, and James Earle Fraser and his wife, Laura Gardin Fraser. By early 1905, it was apparent that Saint-Gaudens was succumbing to cancer. The members of the colony, realizing they soon would lose their beloved founder, mentor and friend, decided to do something genuinely exceptional to honor him. A special event was held on the evening of June 22, 1905, in the form of a masque, which in this case was a classically themed, highly extravagant outdoor play. The setting was a pine grove at the edge of a wooded bluff down the slope from Aspet. In the forest were members of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, hidden so that their musical accompaniment, arranged by composer Arthur Whiting, would effuse mysteriously from the trees. The white plaster and wood set was a fourcolumned altar, flanked by two more columns and large comic masks. In front were benches for the audience, all of whom were invited guests and friends. The event was billed as “A Masque of ‘Ours’: The Gods and the Golden Bowl,” and all aspects of its planning were kept secret from the Saint-Gaudens family, who had promised to keep away from that part of the property. Ninety of the family’s closest friends from the Cornish area formed the imaginatively costumed cast, and there were props galore, some of which survive today.

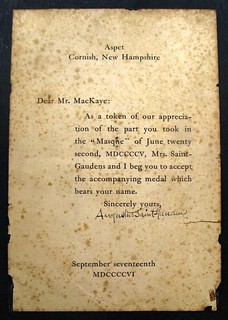

Dress Rehearsal To the modern American, such an extravagant, classical tribute might seem overblown and silly, but Saint-Gaudens did not take it that way. In fact, it was one of the most meaningful moments of his life. A production of this magnitude and beauty, all created in Saint-Gaudens’ honor, could not go unacknowledged, and Gus set to work on a “thank you” as only he could have executed it. Through the last months of 1905, the ailing artist struggled to sculpt a bas relief commemorating the Masque, and, in so doing, created one of his most intricately detailed and text-laden works. The central portion of the design focuses on the scene of the Masque, and shows a temple set in the pine grove. At the sides, comic masks are hung from the trees, which support drawn curtains exposing a lone bench at the left. Below the canopy of the temple is a flaming altar inscribed with “Love Conquers” in Latin. To its right is the winged cherub Amor, playing Apollo’s lyre. The arching panel forming the top of the plaque is framed by a pair of cornucopias and crowned by a depiction of the Golden Bowl given to the Saint-Gaudenses. A rectangular panel below the temple forms the base of the medal, and is punctuated by an image of the chariot in which the couple was transported from the play. Most remarkably, the top and bottom panels are filled with the fully legible names of all 90 colony members who participated in the Masque! At the foot of the plaquette, the sculptor included the inscription IN AFFECTIONATE REMEMBRANCE OF THE CELEBRATION OF JUNE XXIII [sic] MCMV—AUGUSTA AND AUGUSTUS SAINTGAUDENS. For whatever reason, Saint-Gaudens’ recollection of the date was wrong since the Masque took place the day before, on June 22. By early 1906, the artist’s master for the Masque plaque had been dispatched to Europe and had arrived at the Paris establishment of Janvier et Duval. No other “art reduction” medalists could match the quality that came out of this shop, not even the famed Tiffany & Company and Gorham Manufacturing Company, both of which used the ingenious reducing lathe Janvier had invented. (The lathe operated on a principle similar to a pantograph, copying a coinage design from a large model and engraving the image on a smaller master die.) When Gus’ son Homer published The Reminiscences of Augustus Saint-Gaudens in 1913, he stated only that his father distributed the plaquettes during the summer of 1906 “to those who shared in the performance.” Apparently, Gus, in his weakened state, handed them out to friends as the opportunity arose, likely when they visited the artist at Aspet.

Gus died at home on August 3, 1907, and was cremated shortly thereafter in Boston. Below the house, at the bottom of Aspet’s sloping lawn, stood the decomposing temple created for the Masque. Like many of the ephemeral structures built for the great world’s fairs of the period, it was a temporary structure made of reinforced plaster applied to a wooden frame. So important was the Masque’s temple to both the Saint- Gaudens family and the Cornish Colony as a whole that a permanent version was sought. In 1914 the transient stage came down and a white marble temple, designed by the architectural firm of McKim, Meade and White, took its place on the original site. In hindsight, Gus’ choice for the plaquettes’ imagery was eerily prophetic. Today, the marble temple marks the site of the famed Masque, but it also serves as the Saint-Gaudens family tomb, holding the remains of Gus, Augusta, their sons Homer and Louis, and other members of their immediate family. No other collectable medals associated with Augustus Saint-Gaudens are as beautiful or as meaningful to the artist and its recipients. Likewise, none bear such a personal connection, making the Masque plaquettes of great importance to the history of American theatre, the American fine arts movement and the renaissance of American numismatics. For more information about the American Numismatic Association, see:

Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|