PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

VOCABULARY TERM: ALUMINUMDick Johnson submitted this entry from his Encyclopedia of Coin and Medal Terminology. Thanks. -Editor

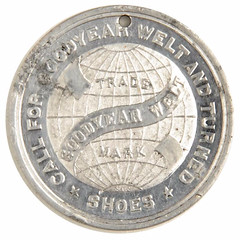

Once aluminum became readily available and inexpensive, by 1880, it was immediately adopted as a low-cost composition for both medals and tokens. A great quantity of electricity is necessary to extract pure aluminum from its ore. Thomas Edison’s inventions of generators and electric transmission provided the necessary electricity. Metalworking firms liked the medal for a wide range of products. Medal makers used aluminum in over 150 different medals for the Columbian Exposition in 1892. This extensive use continued into the 20th century including the 1909 Hudson-Fulton Exposition. Aluminum. A very light-weight metal in silver-white color. It is used in the 20th century for low value coins and cheaply struck medals; however, when first introduced – at the Paris Exposition of 1855 – it was an expensive and exotic composition. Aluminum is quite plentiful, the third most common element in the earth's crust (following oxygen and silicon) and the most abundant metal. However it was not isolated until 1825 by Danish physicist Hans Christian Oersted and even until 1855 was available only in small quantities. It remained high in cost well into the 1880s. Aluminum's light weight was one of its earliest appeals. Napoleon, it is said, liked it for his army's field utensils, and he once gave a banquet in the palace in which the honored guests were served with aluminum utensils and the regular guests with gold! The early process made pure aluminum by sodium reduction of the molten aluminum chloride. It wasn't until the development of the electric power plant (in 1886) that electricity became available at an inexpensive price to make aluminum in a modern way: electrolysis of purified alumina – aluminum oxide. Aluminum became plentiful in both France and the United States at the same time. Aluminum medals. The first medal struck in aluminum was the 4-inch Cyrus Field Congressional Medallion of 1858 for laying the Atlantic telegraph cable. The U.S. Mint at Philadelphia struck six aluminum medals in addition to two in gold from the same dies. At that time the aluminum blanks were just as costly as the gold. The cost of aluminum fell drastically when electrical power became available (by 1890). Another opportunity came at about the same time – the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1892. Of nearly 600 varieties of medals struck for this occasion, over 150 were struck in aluminum. When the metal became available it was immediately and extensively used for medals! The Philadelphia Mint experimented by striking 62 medals in aluminum in 1892 (of some 11 varieties of List Medals) but did little in the metal after that. It was the private companies – like Childs of Chicago, Scovill of Waterbury and Quint of Philadelphia – that struck thousands of medals in hundreds of varieties beginning with the 1892-93 exposition.   From 1893 to 1910, aluminum and white metal compositions were both sold by diesinking and medallic companies in Europe and America, with aluminum at from one-third to two-thirds the cost of bronze. When numismatists issued medals, like Thomas Elder in the first decade of the twentieth century, they would vend many compositions – Elder offered aluminum alongside white metal, pure tin and pewter as well. Tin became scarce during World War I in America, thus tin-based white metal disappeared and was seldom used for coins and medals thereafter. Use of aluminum, on the other hand, increased vastly, virtually replacing white metal as a low-cost composition for medals. As one 1892 medal by Childs states, aluminum was "malleable, tasteless, sonorous, ductile, untarnishable;" it also was excellent for coining. When used as a coinage metal it is usually alloyed 96 1/2 aluminum, 3 1/2 magnesium, which increases its wearability slightly. Once available at low cost, it was immediately embraced by the metalworking industry. Scovill created, in 1894, an aluminum case to house the bronze award medals of the Columbian Exposition. The firm produced 23,000 of both cases and medals. Aluminum coins. The first coins intended for circulation made of aluminum were stuck by England's Royal Mint for British East Africa and British West Africa. It has served as a composition for low valued coins – and widely used for tokens – ever since. It was used as a wartime alloy in World War II and continued for many countries in Europe, Africa, Asia and Latin America. United States has resisted its used because of verification problems in vending machines. While ideal for coin relief, aluminum does not have deep drawing capability. It can be easily struck in low relief coins, but cannot easily be struck in high relief objects. Aluminum is silver-white when freshly cast or polished, but becomes gray when worked, as in coining. In addition to its light weight, aluminum is also different from all other coinage metals in that it can be colored by dyes – forming anodized aluminum. A typical use of anodized aluminum are aluminum throws for parade medals. British spelling is “aluminium” with two i’s. See composition (2).

Looking for the meaning of a numismatic word, or the description of a term? Try the Newman Numismatic Portal's Numismatic Dictionary at: https://nnp.wustl.edu/library/dictionary  Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|