PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

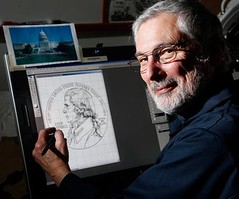

ALL THINGS CONSIDERED INTERVIEWS U.S. MINT ARTISTS This week National Public Radio's All Things Considered program included a great feature on Chief Engraver John Mercanti and the new technology for creating coins at the U.S. Mint. Be sure to listen to the segment online at the link below. Featured in the interview are Joe Menna, Phebe Hemphill and Chief Engraver John Mercanti. See why Mercanti says the switch from traditional sculpting techniques to digital tools was a big leap for his artists. "We jumped a hundred years, literally, with this new technology. And it's so exciting now." -Editor  John Mercanti's title at the U.S. Mint in Philadelphia is chief engraver, but it's a little inaccurate. For one thing, no human at the Mint has actually engraved anything for years. John Mercanti's title at the U.S. Mint in Philadelphia is chief engraver, but it's a little inaccurate. For one thing, no human at the Mint has actually engraved anything for years. This is a time of transition for the design and sculpture department at the Mint, where centuries-old techniques are slowly — and not always easily — giving way to incredibly sophisticated computer technology. So think of Mercanti as an artistic director — one whose standards are so high that the very first thing you see when you get off the elevator by his office is the giant head of Michelangelo's David. "It's an amazing piece," Mercanti says. "Sometimes my sculptors will come out and they'll just stand in awe of the thing." Got a quarter in your hand? Look to see if there's a P on it, right there behind Washington's ponytail. That's the Mint mark for Philadelphia. Once upon a time, Mercanti actually stamped those on by hand. But the steel punches that made their mark on U.S. coins have long ago been replaced by computers. Mercanti's not nostalgic for the old days; he's open to inspiration from the most unlikely sources, like ... Shrek. That's right: Shrek. It was a DVD special feature that convinced Mercanti to call in a Hollywood special effects expert to come teach the Mint's artists how to sculpt in virtual reality. Don't worry about ogres on your coins, though. Remember that head of Michelangelo's David in the hallway? It's not just an inspiration; it's a test. "Every new apprentice or young sculptor that comes in," Mercanti says, "that statue will be taken from the hallway, will be set in the office next door, and that person will sit at the computer and sculpt it. And until they sculpt it, they cannot move to the next level." Phebe Hemphill's cubicle is decorated with action figures, some of which she sculpted herself. Like a lot of artists here, she used to work in the toy industry. On her easel sits a fat plaster disc, about the size of a dinner plate. It's the sculptural model of the congressional gold medal for the Tuskegee Airmen. The figures on the model are swathed in texture. Feathers, leather, facial hair — even a lamb-skin collar. Hemphill uses a variety of tools she's collected over the years to create the different effects. "I have all these weird dental things that you probably don't want to go near," she laughs as she digs through a drawer full of pointy tools. "You can do anything if you just get a pattern down." A couple of computer monitors lurk at the other end of her desk, but Hemphill prefers to sculpt with traditional tools before converting her work to digital. Medallic artist Joe Menna prefers sculpting with a stylus rather than menacing dental tools. He demonstrates by scraping virtual ridges into a portrait of William Henry Harrison on his monitor. "You can see that I'm removing material, just as if I were carving it in clay," he explains. His boss calls Menna the "Yoda" of this technology. Menna says the technology, with its ability to zoom in on tiny detail or create any texture, gives him ultimate aesthetic control. And it's actually changing him as an artist. "The cool thing about working digitally is I can just 'control-Z' — I can just hit the undo button, and it all goes away." He taps his keyboard.  He's so used to sculpting digitally he's found himself reaching for phantom control-Z buttons even when actually working in clay. "Somewhere the wires are connecting upstairs, and I guess I'm evolving with this technology — or devolving, I don't know." He laughs. Menna's enthusiasm for the technology has been gaining converts at the Mint. And there may come a day when there is no more clay and plaster here. But Mercanti knows the important things will endure. "I'm committed to using classical techniques," he says. "Even though we're moving into the digital era, we still maintain the classical psychology." And if Mercanti's artists are ever tempted to stray, there's that imposing enforcer in the hallway — Michelangelo's David. To read the complete article (and listen to the segment), see: Sculpting The Digital Dollar (www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=103013029) Check out the photos here! www.npr.org/multimedia/2009/04/mint/ Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|