PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

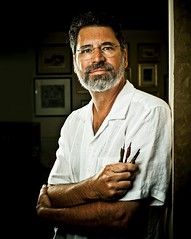

THOMAS HIPSCHEN, BEP PORTRAIT ENGRAVER

Gene Hessler forwarded this great article about Thomas Hipschen, a former portrait engraver at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing. The article came out in October 2010, but we haven't covered it in The E-Sylum. It's long, but very well done - be sure to go online and read it all. Thanks, Gene!

-Editor

Hipschen is considered one of the world's best portrait engravers. "For the late 20th century, he is basically the engraver," says Mark D. Tomasko, author of The Feel of Steel, a history of currency engraving in the United States. But when the Treasury Department rolls out a new $100 bill in February, the engraving on the front—a fuller portrait of Franklin—will be Hipschen's last. The two-centuries-old tradition of hand engraving is fading away. Bank-note artists who cut tiny dots, dashes, and lines into steel plates are putting down their tools and instead using a keyboard and a digital tablet to create images that can be produced in three weeks rather than three months. The move to digital engraving has raised concern about security and even sparked conflict between the Federal Reserve, the central bank that buys the bank notes, and the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, which manufactures them, says Michael Lambert, assistant director for cash at the Federal Reserve Board. Hand engraving has been a security feature of US currency since the early 1800s. Since then, it has been made increasingly complex and intricate in order to frustrate counterfeiters. Hand engraving has remained an important tool for fending off forgeries because engravers' artistic fingerprints—the subtle differences in style found in the tiny dots and dashes—are hard to replicate. Those idiosyncrasies get lost when the work is done on a computer. A magnifying glass held to Benjamin Franklin's coat—which Hipschen lengthened for the new $100 bill—and to the facial and eye area on the left side of the note, reveals lines that are alternatively heavy, thin, dark, and light. Slanted, tic-tac-toe-like crosshatches with dots inside create depth and texture. "It's almost as if the portrait is rising off the paper," says Gene Hessler, author of five books on paper money and engravers. "A master engraver like Hipschen creates this three-dimensional effect better than anyone." Hipschen has spent decades studying engravings—especially those from the 1920s and '30s—to learn ways to use open space, lines, and dots. "There are a million little decisions because there are a million little dots," he says. "It's a very tiny canvas, so all the space has to be put to good use." Hipschen's interest in art was sparked at age eight, when he saw a drawing of a young hare by the German Renaissance engraver Albrecht Dürer in a magazine. "I thought it was the most beautiful thing I had ever seen," he recalls. Hipschen also copied pictures in comic books that his father, a drugstore manager in Bellevue, Iowa, brought home after they didn't sell. Hipschen dreamed of studying art in college but knew that with ten children in the family (he was second-oldest), his parents couldn't afford it. A door to art opened when his cousin Bob Jones, a postage-stamp designer at the Bureau of Engraving in DC, returned home to Iowa to visit and saw Hipschen's work. Jones knew the bureau was searching for an apprentice and encouraged his cousin to apply. Hipschen traveled alone to Washington at age 17 with a bus ticket his grandfather had bought. He sketched a still life, competing with dozens of older artists before winning the post. He credits his youth with helping him get the job: "They wanted someone they could mold." Over the 37 years Hipschen has spent at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing crouched over an angled, lighted table "digging ditches" in steel, often listening to Beethoven, the reproduction of engravings has evolved. At first, the finished plates were hardened in molten cyanide and dipped in oil to cool, a technique used in the 1880s. That practice fell out of favor because it was too dangerous. In the 1980s and '90s, Hipschen continued cutting steel, but the engravings were photo-etched into metal and plastic. By 2000, he was practicing a hybrid engraving method, using both a burin and a computer. Hipschen was the go-to guy for testing the digital technology. He agreed to put down his burin for a keyboard in 2000 and was sent to Lausanne, Switzerland, to learn to operate digital-engraving technology that could create three-dimensional portraits. Computer engraving involves generating lines, then using digital tools to warp, break, angle, taper, and widen them. When the image is complete, the computer runs a laser that cuts lines into plastic to create a metal plate. After experimenting with the technology for a few weeks, Hipschen reluctantly declared it a viable option for making US currency. "Being able to artificially create depth was a great leap forward," he says. "It takes forever to do engraving by hand, but you can do this in minutes. It loses a lot of the character, but I had to admit it worked." Repairing a damaged steel plate from an inadvertent slip can take a week, compared with slips in digital engraving, which can be repaired in seconds.

To read the complete article, see:

Face Value

(www.washingtonian.com/articles/people/17100.html)

The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|