PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

BUSINESSWEEK ARTICLE ON THE 1933 DOUBLE EAGLE

Bloomberg Businessweek published an article about the history of the 1933 Double Eagle, asking "How did a Philadelphia family get hold of $40 million in gold coins, and why has the Secret Service been chasing them for 70 years?"

-Editor

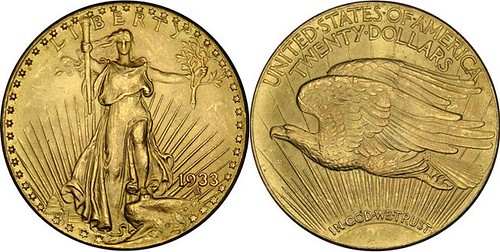

The most valuable coin in the world sits in the lobby of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York in lower Manhattan. It's Exhibit 18E, secured in a bulletproof glass case with an alarm system and an armed guard nearby. The 1933 Double Eagle, considered one of the rarest and most beautiful coins in America, has a face value of $20—and a market value of $7.6 million. It was among the last batch of gold coins ever minted by the U.S. government. The coins were never issued; most of the nearly 500,000 cast were melted down to bullion in 1937. Most, but not all. Some of the coins slipped out of the Philadelphia Mint before then. No one knows for sure exactly how they got out or even how many got out. The U.S. Secret Service, responsible for protecting the nation's currency, has been pursuing them for nearly 70 years, through 13 Administrations and 12 different directors. The investigation has spanned three continents and involved some of the most famous coin collectors in the world, a confidential informant, a playboy king, and a sting operation at the Waldorf Astoria in Manhattan. It has inspired two novels, two nonfiction books, and a television documentary. And much of it has centered around a coin dealer, dead since 1990, whose shop is still open in South Philadelphia, run by his 82-year-old daughter. "The government has been fanatical about seizing and destroying these coins," says Robert W. Hoge, curator of North American coins and currency at the American Numismatic Society. "They're famous because the government has been seizing them since the 1940s." The first phase of the Secret Service investigation would trace 10 1933 Double Eagles to Switt, a reclusive jeweler and coin dealer who, like so many in this story, believed the coins possessed talismanic powers. His only child, Joan Langbord, who worked with him until his death in 1990 at age 95, told the Philadelphia Inquirer that her father "could be obnoxious or irascible. If he didn't like you, he'd throw you out." His business philosophy, she said, was that "the customer was never right; he was always right." "You must understand the Philadelphia thing," says Brahin. "I'm from there, so I can say this: The dealers were crafty, they would do anything to get an edge. If you don't know that, you don't have the right amount of cynicism to analyze the story."

The author lost me at "talismanic powers". But the article an otherwise good job of recounting the tale. I found the financial details interesting in the section about the confiscation of the Farouk specimen from London dealer Stephen Fenton. We in the U.S. know about Jay Parrino, but the article, probably based on court documents, calls him "Jasper".

-Editor

Fenton bought the Double Eagle for $210,000 and arranged to sell it to an American dealer named Jasper Parrino for $850,000. On Feb. 7, 1996, Fenton flew from London to New York on the Concorde and checked into the Hilton. The next morning, he recalls, he tucked the coin into a plastic envelope, put it in his shirt pocket, pulled on a new black cashmere sweater, and hopped into a taxi to the Waldorf Astoria. "It was a routine deal," he says. He went up to a corner suite on the 22nd floor and presented the coin to Parrino, who had already arranged to sell it to Jack Moore, a dealer from Texas, for $1.65 million. Moore had brought along a coin expert of his own. As this expert examined the coin, Fenton began to suspect trouble. "His hands were shaking quite a lot," says Fenton. "I thought he might try to steal it. I was afraid someone was going to come bursting into the room with guns. Well, they did." Moore had contacted the Secret Service and helped them set up an undercover operation. Fenton and Parrino were thrown to the floor by gun-wielding agents who had been waiting in the room next door. "I had an out-of-body experience," says Fenton. "I felt like I was on top of the wardrobe watching. It was like a movie. Then the coin just vanished."

Here's a section about Joan Langbord and the Switt store.

-Editor

This July, eight years after the Langbords say they found the coins, the trial to get them back began at a Philadelphia courthouse, just blocks from the family store on Jewelers Row. Joan Langbord, dressed simply in a tan pantsuit and costume jewelry, took the stand the morning of July 19. She was occasionally teary. She was also sharp-minded, plain-spoken, and slightly irritated. Describing the store, she said: "It looks like a junk shop. But expensive junk. It looks the way it did when my father ran it. His chair is still in the store." Only the first floor of the four-story building is open to those who walk in off the street. Records introduced at the trial show she had visited the safe deposit box many times between 1996 and her discovery of the coins in 2003—including the day before the Sotheby's auction. She said she made the visits to select pieces of her mother's jewelry to sell to a longtime customer and that she never noticed the Wanamaker bag at the bottom. It was only when the box warped and had to be drilled open, she said, that she realized the coins were there. The safe deposit box was shown at the trial: It was about the size of a violin case. After Langbord testified, the judge called for a lunch break, and she and her other son, David, went to the store. It's still called I. Switt & Ed Silver, though her name and that of her business partner are also in gold letters on the front door. She walked in briskly and got right on the phone about a business matter, pointedly ignoring visitors. The old wood and glass counters were filled with jewelry, silver candlesticks, watches, figurines. A cash register from the 1930s sat on another counter. Yellowing family photos hung askew on the wall next to a 2009 Philadelphia Inquirer article about the gold coins.

As we now know, the Langbords lost their case and their coins remain in the government's hands. But the end of the story hasn't been written yet.

The article says the coins have " inspired two novels, two nonfiction books, and a television documentary." I'm aware of the nonfiction books by Frankel and Tripp, but can anyone tell us about the nonfiction books? And where and when did the documentary air - is it available online? -Editor The Langbords are expected to appeal the verdict. Meanwhile, more 1933 Double Eagle gold coins may still be hidden away. "There has always been talk of others," says Armen Vartian, the lawyer for the Professional Numismatists Guild. Hoge, the U.S. coin expert, says: "It's not impossible that more are out there. I haven't seen them. But it wouldn't surprise me."

To read the complete article, see:

Gold Coins: The Mystery of the Double Eagle

(www.businessweek.com/magazine/gold-coins-the-mystery The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|