PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

EXHIBIT: MONEY AND BEAUTYJohn Sallay writes:

There's a literature connection here, too - one of the curators wrote a book called Medici Money which was the inspiration for the exhibit. Here's an excerpt from the review.

-Editor

In northern Italy in the 14th century, bankers had a problem. With the increasing sophistication of currency systems and the growth of international trade, huge new opportunities were afoot to make money by manipulating money. However, there was a catch: Lending money at interest was against the Catholic religion, whose theologians labeled it “usury,” a sin deserving damnation. Canny financiers with one eye on their coffers and the other on what would happen after they were in their coffins came up with some interesting ways around this impasse. One was to exploit slight differences in foreign countries’ exchange rates to generate returns on investment of up to 29 percent. With this practice�"a version of what today would be called arbitrage�"they could claim that technically no interest had been charged and thus be off the hook with the Church hierarchy. Another, very different strategy was to launder the lucre by converting it into art. That would have two outcomes. By commissioning altarpieces and other public religious art, bankers like Cosimo de’ Medici could assuage their guilt and at the same time impress their fellow citizens with their piety. Not only that, but by using financial clout to influence the iconography of these works, they could subtly send a message to the populace that maybe money wasn’t so bad after all, spiritually speaking. By making sure that the Virgin was portrayed in sumptuous garments even if she happened to be in a manger, by having themselves painted into holy scenes hobnobbing with saints and angels, and even by putting religious imagery on coins, the wealthy were engaging in highly effective propaganda for their profession. The fruitful if often uncomfortable relationship between art and money in early Renaissance Florence is the subject of “Money and Beauty: Bankers, Botticelli and the Bonfire of the Vanities,” a fascinating exhibition opening this month in that city’s Palazzo Strozzi museum, co-curated by author Tim Parks and art historian Ludovica Sebregondi. Paintings by artists from Botticelli to Ghirlandaio to Fra Angelico (plus a sampling of pictures by non-Florentines such as Quentin Matsys and Hans Memling) are displayed alongside objects like coins, gold-weighing devices and a bale of raw wool, as well as contemporary financial documents, to tell a complex story from a little-read chapter of cultural history. The idea for the show dates back to a book Parks published in 2005 called Medici Money. “Originally I was asked to write this book by W.W. Norton, who were doing a series on money issues,” recalls Parks, an English-born novelist, travel writer and translator (notably of the wonderful and uncategorizable books of Roberto Calasso) who has been living in Italy for the past 30 years. “‘No way,’ I said, ‘too complex.’” But Parks was persuaded, and the book did well. Several years later, the Palazzo Strozzi got in touch with him and asked if he would be interested in collaborating on an exhibition that would essentially illustrate and extend the points he made about money and art in his book. Since Parks is not an art historian, Sebregondi came on board to lend scholarly expertise and use her curatorial connections to negotiate the impressive roster of loans for the show. The exhibition is structured as a “duet,” and the two curators wrote double captions for all the works. To read the complete review, see: Holy Money (www.artandantiquesmag.com/2011/09/holy-money/)

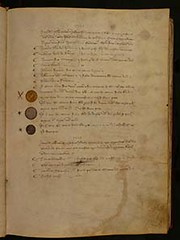

Vanna Arrighi published an article on the exhibit (taken from the exhibit catalog) in this week's Coins Weekly. Highlighted is an item for numismatic bibliophiles and researchers.

To read the complete article, see: Striking Coins in Florence (www.coinsweekly.com/en/Article-of-the-week/5)

For more information on the exhibit, see:

Money and Beauty. Bankers, Botticelli and the Bonfire of the Vanities

(www.palazzostrozzi.org/SezioneDenaro.jsp?idSezione=1214)

The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|