PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

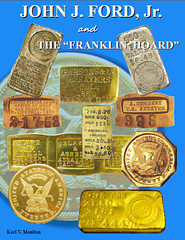

BOOK REVIEW: JOHN J. FORD AND THE FRANKLIN HOARD

John Kleeberg submitted this review of Karl Moulton's book about John Ford and the Franklin Hoard.

-Editor

This book provides a double biography of John Ford and Paul Franklin and the forgeries they marketed, but it is oddly arranged, which makes the author’s arguments difficult to follow. It resembles a scrapbook more than a proper book. The documents are arranged in strict chronological order, with many reproduced attractively in full color. The chronological order reveals some new insights – it appears that the reason so many USAOG prooflike $20s hit the market in such a large quantity in a short period of time in early 1958 (a crucial mistake by the forgers) is because Ford realized that F. C. C. Boyd was sick and dying, and Ford needed the cash so he could lock up the coins and paper money in the F. C. C. Boyd Estate. The book makes for interesting, but not always enjoyable, reading. The portrait of John Ford that emerges is extraordinarily dark and negative. On page 514 the author even goes so far as to call John Ford a psychopath. Ford once said that upon the creation of NASCA he advised Douglas Ball to go into business with Herb Melnick, saying “He is a wolf, but he will protect you from the other wolves.” While reading this book I couldn’t help but thinking that that must be the explanation why a decent guy like Charlie Wormser would work with John Ford for twenty years. The author had the co-operation of Gerow Paul Franklin’s family, which may explain the attempts to whitewash Franklin. The author suggests that perhaps Franklin did not make the fake items, they were actually made by someone else – maybe Peter Rosa, maybe Kenyon Painter, maybe Hedgepeth, maybe Diehl – ignoring that of those persons, none, not even Rosa, possessed the sophisticated metalworking skills that Franklin did. Moreover, the provenances of the fake items trace back again and again to Ford and Franklin, and not to anyone else. The author argues that because Franklin was sentenced to probation and not imprisoned, he had never been convicted of counterfeiting. This is quite simply incorrect. The author is right in his observation that an arrest is not the same as a conviction, but a defendant cannot be sentenced to probation or to anything else without being convicted first. After Franklin was arrested in July 1943 for draft evasion and firearms offenses, the author tells us that Franklin spent over a year in Lewisburg penitentiary (pages 111-13). That is the type of sentence that is meted out to a defendant who has a prior criminal history, whereas a first-time offender would be offered probation. Another incorrect interpretation by the author, in my view, is his belief that when Franklin made trips out West he was traveling out to buy the fake bars and coins. I disagree. Franklin made the items back in the East. Franklin’s trips out West were not to buy the manufactured products, but to acquire illicit gold – either from contacts in the mining industry (Franklin was a member of the Arizona Small Mine Owners Association), or by smuggling bullion from Mexico. It is a pity the book was not copy-edited more thoroughly, for there are quite a few misspellings and errors in grammar and syntax. I can also add some additional details about the origins of the false Mexican gold bars. The author suggests that they were inspired by the fake “Father Kino” bars that were sold as souvenirs throughout the Southwest. This is plausible, but there was a more direct inspiration. Harry Rieseberg wrote books about treasure hunting that were fiction masquerading as fact. He also wrote the script for a 1953 movie (from Universal-International) about treasure hunting, “City Beneath the Sea.” While going through Gordon Frost’s library I came across a collection of promotional photographs from movies with numismatic content. One of the photographs was for “City Beneath the Sea,” dated 1953, and it shows the Mexican HISP ET ID bars, which are clearly movie props, mere blocks of gold painted wood. The caption reads: “EVER SEEN SUNKEN TREASURE? Here is $28,000 worth, in gold, found during the undersea peregrinations of Lieut. Harry E. Rieseberg, famed treasure hunter, whose experiences on the ocean bed near the sunken city of Port Royale [sic] provide the background for his authorship of Universal-International’s Technicolor adventure, ‘CITY BENEATH THE SEA.’”

Reproductions of this photograph may be found in Rieseberg’s “Treasure of the Buccaneer Sea” (1962) and in his “Fell’s Guide to Sunken Treasure Ships of the World” (1965). These movie props of 1953 served as the model for the subsequent gold fakes. The book reproduces correspondence not only from the files of John Ford, but also from Gerow Paul Franklin, Eric P. Newman, and Q. David Bowers, which adds immeasurably to the book’s value. Eric Newman’s notes from his interview with Kenyon Painter are particularly helpful. Some interesting quotes: From a letter of John J. Pittman to John Ford, November 26, 1958 (page 439): “One of your ‘friends’ got drunk at one of the conventions and intimated that the dies were still in existence and that the pieces may have been manufactured in the eastern part of the U.S. within the last several years by Paul Franklin for you, and moreover, that you had been bragging that you had taken me for a pigeon with respect to the 1853 U.S. Assay Office $20 proof.” (Pittman subsequently returned the prooflike USAOG $20 to Ford.) Note this quote from Ford in Coin World, September 6, 1999 (page 750): “Ford insists he never had contact with a smelter and questions why a refiner would have risked selling him gold, when it would have meant risking his license to operate at the time.” Contrast that with what Gerow Paul Franklin writes in a letter of 1962 (page 486): “On your inquiry regarding the placer gold I have a friend out West from whom I have obtained some nice gold specimens I will write him and inquire as to how much it costs now. I have paid as high as $53.00 an ounce for dust and small nuggets, as high as $75.00 to $80.00 for large nuggets and leaf gold specimens these of course are more rare.” A further correction: The John J. Ford selling counterfeit money in 1891 (pages 823-824) cannot have been John Ford’s father. John J. Ford, Jr., was born on March 5, 1924, and in the 1930 Federal census his father’s age is given as 40 years old, i.e. John J. Ford, Sr., was born circa 1890. The book will appeal to the “completist” who wants to collect every single book about territorial gold. The book assembles in a single convenient volume ephemera that can be difficult to track down, even if you already own them (“Now where did I put that photocopy that I was just looking at last week?”). It is good of the contributors to this volume to share all this data with us, and for the author/editor to have assembled it in such a convenient form. But the greatest appeal of this book is that a few decades ago, none of this information was allowed to be published at all. Ford so intimidated Coin World and Numismatic News that there was no coverage of Ted Buttrey’s exposé of the false Mexican gold bars, which finally appeared in Memorias de la Academia Mexicana de Estudios Numismáticos. As Ford wrote in a letter of October 3, 1979 (page 666): “This article was published in English, in a Spanish language publication, presumably for clandestine distribution in the United States.” This is quite true – most numismatists had to be content with bootleg photocopies. Only a few lucky persons were trusted enough to be given an original from the source speakeasy (Eric Newman’s basement). To those of us who remember that period, it is amazing that Moulton has been able to publish this book and that we are allowed to read it.

I asked John for some further discussion of the “City Beneath the Sea” publicity photo, which underscores the huge potential research value of numismatic ephemera. Many thanks for Gordon frost for saving it and providing our generation with a new clue to this mystery. Here's his response.

-Editor

In the 1950s there were false silver bars being sold in souvenir shops in the Southwest. These bars are not very convincing - they bear a cross and the letter V, they are very simple in their designs, they are made from debased silver or maybe tin. They were promoted as having been the products of mining efforts by the Jesuits in the 17th and 18th centuries in New Mexico and Arizona, and attributed to the Jesuit priest Father Kino. These are just wild stories; the Jesuits did a lot of good work on the northern frontier of New Spain, but one thing they did not do was to run mining operations. Karl Moulton suggests that these bogus bars were the model for the false Mexican gold bars. I do not think this is quite correct, although these bars and the Kino stories may have inspired another false ingot, the Tubac ingot that Buttrey wrote up in the Numismatic Chronicle. There is, to my mind, a more direct inspiration for the false Mexican gold bars. Meanwhile, Harry Rieseberg was making up his stories about treasure hunting and persuaded Universal to convert them into a motion picture ("City Beneath the Sea"). As part of the promotion, Mexican gold bar props were made out of wooden blocks in 1952-53. Photographs of these bars were circulated by Universal's publicity department, and Rieseberg re-used them in at least two of his books. Although Rieseberg claimed the bars were gold, if you look closely at the picture it is clear that they are gold painted wooden blocks. They resemble the later false Mexican gold bars with the shield and HISP ET ID except that the letter "S" is reversed and, of course, they are wood, not gold. On September 1, 1954, as published in The Numismatist, Paul Franklin showed up at the Brooklyn Coin Club and exhibited a gold Mexican HISP ET ID bar (see Moulton page 253). Thereafter the bars were sold/traded by John Ford all over the U.S. numismatic community - to Wayte Raymond, F. C. C. Boyd, Werner Amelingmeier, Mrs. Norweb, Stack's, Josiah K. Lilly, and ultimately the Smithsonian after the government acquired the Lilly collection. Ted Buttrey condemned these bars as fake at the International Numismatic Congress of 1973 held in New York City and Washington, and his paper was later published in the Mexican journal Memorias de la Academia Mexicana de Estudios Numismaticos. This explains why there are a group of false Mexican bars in Rieseberg's work that are not traceable back to John Ford and Paul Franklin; the wooden blocks painted gold, made to the specifications of Rieseberg and the Universal studio, served as the model that Franklin used to make false Mexican bars out of real gold. To read an earlier E-Sylum article, see: BOOK REVIEW: JOHN J. FORD AND THE FRANKLIN HOARD (www.coinbooks.org/esylum_v16n24a05.html)

Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|