PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

BOB EVANS ON THE SS CENTRAL AMERICA DOUBLE EAGLES

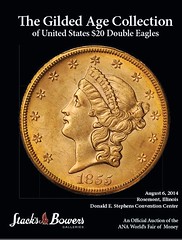

In a preface to the August 6, 2014 Stack's Bowers sale catalog of the Gilded Age Collection, SS Central America curator Bob Evans discusses his numismatic journey from child collector to micropaleontologist, to expert numismatic curator and cataloguer.

Here's an excerpt.

-Editor

But it didn’t last. My collecting interests drifted toward picking up fossils and interesting rocks, most of them found scanning the limestone gravel of local driveways, parking lots and construction sites in the eastern suburbs of Columbus, Ohio where I was raised. I followed this interest into college, ultimately receiving my Bachelor of Science from the Ohio State University Department of Geology and Mineralogy. For my senior thesis I worked through a microscope, studying and measuring the details of animals that lived 400 million years ago. I was still a guy interested in fossils. Who could have predicted that this background was a perfect preparation for what was thrust at me from the deep Atlantic. On September 12, 1857, the S.S. Central America had sunk far off the Carolina coast, carrying to the depths the greatest lost treasure in United States history. In 1983, Tommy Thompson was my neighbor. He was a quirky, eccentric, innovative engineer who professed a dream of opening up the deep ocean frontier by focusing on its known resources, including valuable shipwrecks. The full story of our collaboration is beyond the scope of these paragraphs, but I joined his project, as of 1983 centered on the search for the fabled “Ship of Gold” and its storybook treasure. In 1988 our project hit pay dirt, finding the shipwreck site and with it not only a dazzling pile of gold, but also an incredibly rich numismatic time capsule. Think of it—thousands of Mint State double eagles! Frozen on their pristine surfaces lay the physical record of the industrial arts of the United States Mint of the 1850s. I developed a technique to safely and responsibly remove the rust and mineral deposits obscuring these beauties. At first I was simply dazzled by how new they looked; in particular many of the 1857-S double eagles looked as if they had been made yesterday. But as I shared this material with other far more experienced eyes and minds, I began to appreciate just how special this treasure was. James Lamb of Christie’s was the first real numismatist to see the treasure, visiting my shipboard laboratory, and declaring his experience to be the event of his or any other numismatist’s lifetime. I soon learned this was not mere hyperbole. James introduced me to John Ford and to Walter Breen, top experts brought in to lend their own thoughts to the increasing body of knowledge. Breen wrote an article for The Numismatist based on his examination of a few dozen pieces of gold at Christie’s New York office. The treasure was speaking volumes, and I was learning its language. Breen introduced me to the existence of die varieties, and I was delighted to find that here was a place where my micropaleontologist’s skill set could apply. As I conserved more coins I became familiar with the more common varieties. Actually, I found the identification of varieties to be relatively easy. Whereas like any living things, the features of fossils could vary through infinite degrees of tiny differences, coins were clearly either one variety or another, with no ambiguity. The impressions left by those tools at the mid-19th century mints were immediately distinguishable. No question about it. There were coins that showed tiny bumps on Liberty’s face, and I realized that these were the impressions left by a die that had rusted slightly, leaving me a little chilled by the idea that I could be looking at the result of a workman’s day-ending absentmindedness, forgetting to oil the dies for the overnight hours. I was seeing the footprint of a misty San Francisco night over 14 decades ago! Here was that fog, etched in gold for all time. There were other groups of coins where the same variety showed successive die states, the devices receding into the fields, or the edges of the die cracking and the cracks propagating until ultimate replacement. I found year-transition dies, where the reverse of one year continued to be used with the next year’s obverse, at least for a time. Each new discovery was a personal delight. As I became more familiar with numismatics, I saw that this sort of research had long before been introduced and refined with other series, obviously with Sheldon numbers for early copper, the VAMs for Morgan dollars, and similar cataloging of Liberty Seated and other series. The huge sample of double eagles in the S.S. Central America treasure, concentrated briefly in one conservation laboratory, made it possible for me to begin this process for the largest denomination of circulating United States coinage. To read the complete catalog, see: The Gilded Age Collection of United States $20 Double Eagles (media.stacksbowers.com/VirtualCatalogs/2014/Stacks-Bowers-Galleries/aug2014-chicago-ana/SBG_Aug2014_ANA_GildedAge_Catalog_LR.pdf)

The builder (and now consignor) of the Gilded Age Collection, Rob Galiette adds these comments on the condition rarity of these early double eagles. Thanks.

-Editor

Rob Galiette writes: People need to understand that there was almost no higher-grade double eagle material available for the production years prior to 1858, there not even being Proof $20 gold options prior to that date. I’m working on a brief research summary of the major gold auctions conducted during the 58 years when Liberty Head double eagles were produced between 1850 and 1907. During that time only one of these auctions, Woodward’s Heman Ely auction in 1884, had a circulation strike double eagle: a circulated 1850 $20 coin. In the 85 years from 1850 through 1935, when Perry Fuller auctioned the Baltimore hoard of gold coins, the sixteen largest collections of U.S. gold at auction had a total of only eight Mint State Liberty Head double eagles among all of them. As a further note of interest concerning these eight Mint State coins, remarkably the first one of them in these sixteen landmark gold collection auctions did not appear until 1911, four years after double eagle production ceased in 1907.. The entire Liberty Head double eagle series is unlike any other in U.S. numismatics. It’s been necessary to treasure-hunt Liberty Head double eagles years after the original mintages of these coins -- from foreign banks, hiding places, the sea floor, etc. Dave Bowers and I explain in this year’s double eagle book that paper currency introduced as “Greenbacks” by the Federal Government in 1861 traded at a discount to gold until they reached parity seventeen years later at the end of 1878. It might have required, for example, 160 paper U.S. dollars to purchase $100 in gold coin; or at another point, perhaps $220 or $135 in paper currency to purchase $100 in gold coin. The exchange rate regularly varied. There accordingly was a great preference for gold. The subject of this exchange disparity, as well as the California Gold Rush, continually were in the news. Liberty Head double eagle gold coins in those years had almost no numismatic premium over face value. Even Proof gold Liberty Head double eagles sometimes sold at that time for only a dollar or two over face value. Therefore, you’d think that these large and impressive coins, by virtue of their low cost, beauty in Mint State, and historic significance, would have been included in landmark gold coin collections of those decades, and subsequent ones. Yet it’s remarkable, for example, that 150 years after their production even the ten paired Civil War year P and S-mint $20’s from 1861 through 1865 never have been offered, until now, as a group in Mint State. Over 8.2 million U.S. double eagles were coined through those five years. Early double eagles are challenging to obtain even in circulated condition, because so many of the coins were melted and re-coined when they reached Europe at the time, well before the U.S. melting of its own gold coinage in 1933. Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|