PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

ZIMBABWE'S DOLLARS

The Medium blog has a nice article on Zimbabwe's dollarization, scrip change notes and souvenirs of hyperinflation. Thanks to Kavan Ratnatunga for passing this along.

-Editor

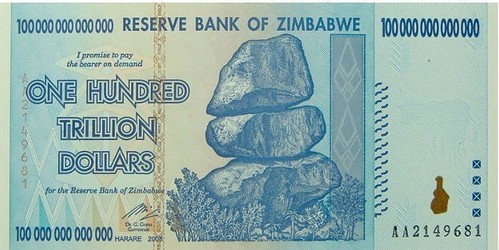

Anyone who has been to Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe has had the surreal experience of seeing a real $100 trillion dollar bill. The world’s largest waterfall now competes with the world’s largest banknote, and the latter have steadily replaced carved wooden elephants as the quintessential souvenir pushed by hawkers around town. When I visited in October 2011, Zim dollars had been out of circulation for nearly 3 years, a casualty of the country’s losing bout with hyperinflation, which escalated as Zimbabweans (and currency traders) became less and less certain of the country’s future, and therefore of the value of its currency. When inflation reaches a certain level, the lack of confidence in the local currency becomes pervasive, and the yo-yo’ing gets worse and worse every time new bills are released. By the summer of 2008, months before the Zim dollar was taken out of circulation, inflation reached 231 million percent, and the government stopped keeping track. By November estimates reached a number I can’t even pronounce: 89,700,000,000,000,000,000,000%. By 2009, Zimbabwe’s economy was almost completely “dollarized,” with most retailers accepting only foreign currency. Now, the country runs on American dollars as worn and beaten up as any money you’ve ever seen, because the US Mint isn’t there to supply Zimbabwe with fresh bills. American change — quarters, dimes, nickels — is so rare that shopkeepers are likely to refuse it. But in a country where most people live on less than a dollar a day, having a dollar as your smallest denomination has obvious problems. For transactions involving uneven dollar amounts, stores unflinchingly provide you change in two currencies: American dollars and South African Rand, worth about 10 cents. If a cashier is short on Rand, he’ll hand you a slip of paper promising, say, 63 cents in store credit, or — no joke — the equivalent value in lollipops, bubblegum, or mints. Officially, Zimbabwe now has four legal currencies, the third and fourth being the Euro and the Pound, but in practice, neither is nearly as common as hard candy.

The article goes on to describe how the old hyperinflationary notes have now become the base of a booming souvenir trade.

-Editor

Namotolo, a softspoken man with hollow cheeks and a startlingly deep voice, is one of a few dozen people in Victoria Falls who makes his living selling Zim dollars as souvenirs. For $10 US, you can buy a whole set — ranging from $100 trillion down to 100,000, which seems almost banal by comparison. “We almost came to the octillion,” Namotolo told me in his singsong Shona accent, stretching octillion to four clear syllables. “Twenty seven zeroes. Do you know that one? The green one? “Nobody knows,” he went on, “but we know because we are surviving on selling these notes.” The currency was abandoned before octillions made it out of the bank, but you could still find one on the souvenir market, he said, if you looked hard enough. Along several blocks of restaurants, gift shops, and safari outfitters, men like Namotolo stand curbside tempting tourists with wads of billion dollar bills. “The time we started,” Namotolo said, “we were selling some wooden carvings and some stone carvings on the street, you see? Some tourists started asking for Zim dollars — they started buying Zim dollars when it was still working, while they were in circulation.” Suddenly, Zim dollars, viewed as artifact rather than currency, became a source of foreign exchange. The shift not was without irony: at the time, the utter lack of foreign currency available to Zimbabwean banks was a key factor driving the government’s incessant printing of new money. If not for buying them as souvenirs, tourists had essentially no contact with local currency, and you could tell from Namotolo’s voice what a revelation this had been. “These things!” he said. “You could use them, sell them as souvenirs.” Three years later, the trade for Zim dollars turned on tourists’ reliable fascination with Zimbabwe’s economic demise, and on the reluctant disillusionment of thousands of civil servants and farmers living in the countryside. These are Namotolo’s suppliers, people who saw their life savings evaporate during the inflation crisis. As inflation skyrocketed in 2007 and 2008, teachers’ pensions became worthless overnight, and, stacks of large bills hidden under mattresses shrank to the equivalent of so many pennies, or even less.

To read the complete article, see:

My brother went to Zimbabwe, and all he got me was 100 trillion dollars

(medium.com/african-makers/my-brother-went-to-zimbabwe-and-all-he-got-me-was-100-trillion-dollars-1b94cf1916b7)

The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|