PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

MACHINE-ENGRAVED GEOMETRIC PATTERNS ON BANKNOTES

If you're not a member of the American Numismatic Association, you're missing out on a great periodical - The Numismatist. The September 2014 issue has a number of nice articles. Here's an excerpt from one I found particularly interesting. Andrew Hurle's article Absractions of Value focuses on a prominent but little-understood area of paper money production - machine-engraved geometric patterns.

-Editor

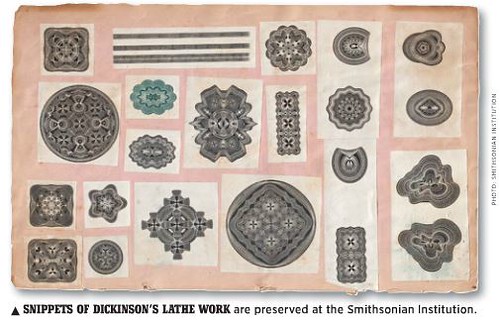

ABSTRACTIONS of Value

WHEN NUMISMATIC LITERATURE approaches the subject of bank-note aesthetics, it tends to give more attention to pictorial features than abstract or ornamental embellishments. This is despite the fact that some of the most instantly recognizable motifs printed on money are geometric patterns created by a machine, rather than images incised by an engraver. Mechanical engraving grew out of the “reproductive engraving” industry in the late 18th century as a practical means of speeding up repetitive tasks, such as tooling intricate backgrounds and textures. However, automated and more abstract engravings were developed specifically for securing the credibility of printed money. Ornamental hybrids of human computation and mechanical execution, these abstract designs are under-appreciated. Before they appeared on paper money, such complex abstractions were virtually unknown in both the fine and the decorative arts. (The closest predecessors were tracings made using relatively simple devices, such as the “geometric pen” invented by Italian mathematician Giambattista Suardi in the 18th century.) In the 1830s, machined patterns became popularly understood as signs of authenticity, helping people recognize and trust financial instruments, such as bank notes and bonds. For this reason, their function is intrinsic to the notion of “bearer security”: they certified printed money by establishing the conventions for its appearance, and encouraged its circulation with no need for personal endorsement. Engraved scenes and characterizations worked toward the same ends, but by slightly different means. This is reflected not only in how they looked, but also in the manner in which they communicated a sense of value. Portraits and vignettes always are anchored to geographical locations and political circumstances. They convey stories about people and events that contribute to a nation’s identity and showcase the aesthetic standards of particular cultures. For example, consider allegorical figures of Science and Commerce, as well as archetypal images of prosperity, such as factory smokestacks and pastoral fields. Such images quickly establish the notes’ 19th-century provenance. Even the portraits of stately bearded gentlemen and grizzled war generals—men who should command respect for eternity—are indicative of a stylistic currency that has depreciated over time and distance. (The depiction of George Washington as a semi-nude Greek god is a good example.) Machined abstraction, on the other hand, expresses the workings of a technology, rather than the sentiments of the picturesque. It provides no convenient reference to personalities or events, but is accepted simply as a means of deterring counterfeiting. Perhaps this is one reason why its history and the extent of its use is less understood and researched.

Abstractions are more difficult to analyze than pictures, and there is little consistent terminology to describe those that decorate money. In some cases, technical terms apply to the basic trajectory of the lines, such as sinusoidal (waves) and epicycloidal (loops), and identify some basic con figurations. A “rosette,” for instance, describes the concentric accumulation of waves (or “petals”) in an elliptical arrangement, while “straight line ruling” indicates the engraving is laid in rows. Unlike other types of decorative arts, however, there are no words, like “acanthus leaves,” “caryatids” or “volutes,” that connect machine-engraved patterns to any tangible object in the natural world. (The word “guilloche” often is used as a general description, but this is a borrowed term that properly refers to the interlacing of bands found on Greek and Roman architecture, rather than to any configuration of printed line.)

For more information, see:

http://money.org/the-numismatist

The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|