PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

WHY DO WE NO LONGER USE $1,000 BILLS?

A December 23, 2015 piece from Marketplace.org asks, "Why do we no longer use $1,000 bills?" Matthew Wittmann of the ANS

is quoted here, as is Dennis Forgue of Harlan J. Berk, Ltd. Nice job, guys. -Editor

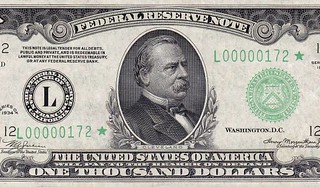

In the early 1900s, a bottle of Coke cost a nickel, a Ford Model T could fetch $290, and some apartment rents dipped as low as $4 a month. So it might sound intuitive that now we’d have larger bills to make the purchasing process more convenient, more efficient. That’s why listener Rabin’ Monroe wrote in with the question, “Why aren't we using $1,000 bills anymore? Seems more appropriate to use them now than back in the early 20th century.” The highest value of denomination currently in production is the $100 bill, but in decades past, the Federal Reserve has printed $1,000, $5,000, $10,000 and even $100,000 bills. The $1,000 bill’s history

The Continental Congress—a body of delegates representing the thirteen colonies—began issuing paper money, which included the $1,000 bill, to help finance the Revolutionary War, said Matthew Wittmann, an assistant curator at the American Numismatic Society, an organization that studies coins and currency. But back then, it was only worth a fraction of that actual value, he added. “So this $1,000 note seems incredible, but what it reflects is actually how little paper dollars were valued,” Wittmann said. “It might only have been worth $20 in ‘real’ hard money at the time.” The U.S. government didn’t actually officially print $1,000 bills until the start of the Civil War, said Dennis Forgue, a numismatist who works at coin-dealing company Harlan J. Berk, Ltd. Lee Ohanian, an economics professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, said the bill was used to rapidly purchase supplies like ammunitions during the war. In the decades after,the $1,000 bill and other large-denomination currencies were mostly used in real estate deals or interbank transfers, Ohanian said. “They facilitated really, really large financial transactions that primarily were being carried out between banks or other financial intermediaries,” Ohanian said. “So it made life a little bit easier.” Illegal activity

Forgue said President Nixon thought these denominations of notes would make it easier for criminals to launder money, which then led to his order for their elimination. Plus, turns out churning out $1,000 bills just wasn’t very cost-efficient. To produce them, you’d have to go through the trouble of engraving new plates for very small production runs, Wittmann said. Running off a lot of $1 notes is more cost-efficient than producing comparatively few $1,000 notes, he added. To read the complete article, see:

Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|