PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

DID COL. GREEN ESTATE BURN RARE BANKNOTES WORTH $1M?

The Atlas Obscura blog is informative and entertaining. On February 16, 2016 one of their articles touched on a numismatic topic -

an episode many collectors may not be aware of. Gotta love the headline: "THINK KANYE’S BAD WITH MONEY? THIS FAMILY LITERALLY BURNED

$1 MILLION" -Editor

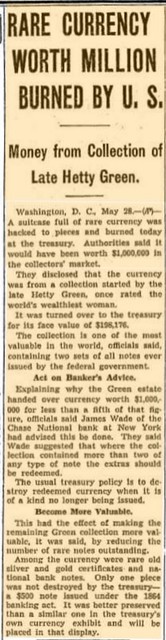

In fact, after the Treasury took possession, the Associated Press reported, that cash was “hacked to pieces and burned.” The Treasury did keep one bill—a $500 note that the Treasury had issued in the mid-19th century. It was in better condition than the one in the official Treasury collection. Far from an example of government overreach, this strange incident of money-burning was a canny strategy to make the estate of one Colonel E.H.R. Green even more valuable. It was also a preamble to the demise of one of the greatest currency collections ever assembled. This collection was begun by Hetty Green, the only female tycoon of the Gilded Age. Green was famously tight-fisted with her money—she lived in Brooklyn and Hoboken to avoid paying Manhattan taxes—but found physical bills fascinating (and valuable) enough that she started amassing rare currency, along with regular old money. Although coin collecting had been in vogue for centuries, until the 1940s, collecting paper money was rare. Even then, coin collecting was more prestigious. “Until recently, the derisive term used by coin collectors to characterize those of paper money was ‘ragpickers,’” says Art Friedberg, co-author of Paper Money of the U.S. Colonel Green, Hetty’s son, inherited half of her fortune and was himself a famous coin collector. After he died in 1936, though, neither his sister nor widow, fighting over his estate, seemed interested in the family hobby. At the time, the Green currency collection contained two of almost every banknote ever issued by the U.S. government, the AP reported. This was one of the two “greatest collections of paper money ever formed,” Freidberg notes in his book. The other belonged to Albert A. Grinnell, and when it was broken up, beginning in 1944, it took seven auctions to sell it all off. Before selling the Green collection, though, the estate’s advisor, James Wade of Chase National Bank, convinced the family to prune back the collection, so that it contained only one of every bill. Treasury policy was to destroy currency no longer in circulation, and by turning over those rare bills, the Green estate had a chance to increase the value of the remaining bills even further. (The Treasury still will destroy bills that are damaged or otherwise unusable.) It was good advice, since the Green estate did have money to burn. According an appraisal, Friedberg says, the collection had 61,664 pieces of paper money at the time. “Whatever was ostensibly burned was a drop in the bucket and, indeed, would have made what was left more valuable,” he says. A few years later, in 1942, the collection was sold privately. While auctions mean auction catalogues, private sales leave no public records, so it’s impossible to know what exactly what was in that collection—or what rare bills the Treasury burned. Since then, currency collecting has become popular (and competitive) enough that no new suitcase filled with money has ever rivaled the Greens'.

I don't ordinarily publish the entire text of articles from other publications, but it's short and I want to discuss a few things

about it. First, I congratulate the author for unearthing this event and especially for citing the source - the article links to an

Associated Press article in the May 29, 1937 Chicago Tribune, which I've included here.

Second, I've read two biographies of Hetty Green plus multiple articles and I've never seen her characterized as a coin or paper money collector. The term most often associated with her is "miser", which is not inconsistent with accumulating piles of paper money, but doesn't conjure the methodical nature of a true numismatist. While her son Col. Green may have inherited some rare notes, there is no evidence that he inherited an organized collection - what ended up in his estate was largely assembled or purchased by him following his mother's death. Third, while the 1937 article correctly states the Treasury's "usual policy" of burning obsolete notes, it does not provide direct evidence of this. Often the reality is more nuanced. So I reached out to some smart E-Sylum contributors including Roger Burdette, co-author of Truth Seeker: The Life of Eric P. Newman. His response is below. Newman knew Col. Green and purchased the bulk of his numismatic collections in partnership with dealer B. G. Johnson. Thanks also to Roger's fellow authors Joel Orosz and Len Augsburger. -Editor Roger Burdette writes: An unfortunate incident involving the Col. Green Estate occurred in 1937 when paper currency worth approximately $1,000,000 to collectors was redeemed for face value of $198,176 and burned. The money was turned over by assistant cashier James M. Wade of the Chase National Bank, which was holding the Col. Green estate for safekeeping. According to a bank spokesman at the time, Wade suggested that wherever the collection contained more than two of any type of note, the extras should be redeemed. This was supposed to have had the effect of making the remaining Green collection more valuable by reducing the number of rare notes outstanding. Curiously, Wade was an active collector of U.S. paper currency, and in 1956 his outstanding collection of rare notes was sold to Aubrey Bebee. From there, some of the notes were donated by Bebee to the American Numismatic Association Museum. One wonders if a certain degree of self-interest motivated Wade’s recommendation. It is also curious that no one at the bank or the legal trustees for Green’s estate appears to have objected. This was in addition to the Treasury Department’s requirement that all Gold Certificates in the collection be redeemed for face value. James M. Wade was a coin collector and assistant cashier of Chase National Bank, was also executor of the estate of Annie Woodin, widow of William Woodin, and sold off Woodin’s patterns to F.C.C. Boyd in 1941 at bargain prices. Regarding Hetty Green as a collector, Joel Orosz adds writes: I completely agree with Roger. Hetty Green saved items like old sleighs from her childhood, but I've never run across any evidence that she was in any way a collector of coins or paper money. To read the complete article, see:

Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|