PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

U.S. MINT HUBBING DIES IN 1793

The publication of the August issue of The Numismatist from the American Numismatic Association has shamed me into finally highlighting a great article in the June 2017 issue by Bill Eckberg on the use of hubbing dies in early America. Here's an excerpt.

-Editor

Hubbing Dies in the Earliest days of the United States Mint

Hubbing is the process

of creating multiple

dies that bear the same

elements. A hub is a

raised punch used to

impress a design into a die.

Though the terms

“punch” and “hub”

often are used interchangeably,

for the

purpose of this article

the difference between

them is a matter of

size. A punch is small

and features a single

letter, numeral, leaf or

other ornament; a hub

carries a larger device,

such as a head, wreath

or eagle, or even all

the images that appear

on one side of

a coin.

Hubbing is thought to

have begun in the United States

with the creation of obverse and

reverse dies for some Connecticut state coppers. The first

time the U.S. Mint used a hub

for the main device was believed

to have been in 1793 for

the Liberty Cap cents.

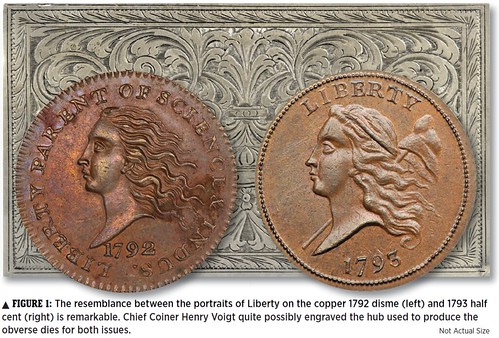

Since at least the late 19th

century, numismatists have remarked

on the artistic similar ities

between the 1792 disme pattern

and the 1793 half cent, suggesting

that they were executed by the same hand, namely Voigt’s.

Recently, I delved into this mystery.

Could the resemblance be

more than coincidental?

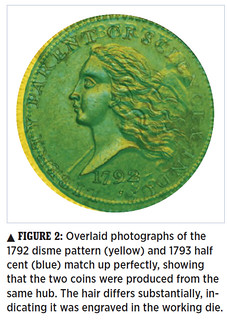

The main variance between the

dies (and probably the reason

nobody has noticed their exact

match) is the hair.

My findings show conclusively

that a single hub was used

for both the 1792 disme pattern

and 1793 half cent obverses.

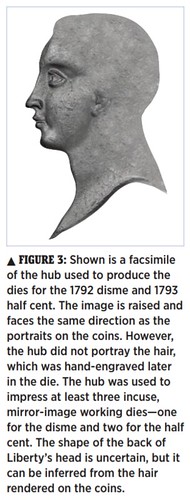

Figure 3 shows how that hub

probably looked. Although the

hair was not defined, the approximate

shape of Liberty’s head can be determined.

The question remains: Why

would Voigt have prepared a

hub for the disme pattern in

1792? We can’t know for sure,

but the simplest explanation is

that he was experimenting.

Voigt must have known that the

hubbing process could produce

a number of nearly identical

dies and simply gave it a try.

Since he had successfully made

and used a hub, I wonder why

he reverted to hand- engraving

the Chain cent obverses. Of

course, I can only speculate, but

perhaps he was concerned that

a larger hub might not be effectual.

How ever, Voigt obviously

didn’t hesitate for long, as he

developed a hub for the Wreath

cent obverse within days of the

Chain cent minting and re-used

the leftover hub from the previous

year’s disme pattern for the

half cents.

In retrospect, Henry Voigt

deserves immense credit. Accepting

a temporary position

as the U.S. Mint’s chief coiner,

he experimented with hubbing

as early as 1792. He truly was a

remarkable and talented man,

without whom the mint might

not have succeeded.

For more information about the American Numismatic Association, see:

|