PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

THE COLONIAL FRENCH SOL OF 1767My old Pennsylvania friend Paul Schultz published a nice article on the 1767 French sol in the October 2017 issue of The Numismatist, the official publication of the American

Numismatic Society). With permission, here's an excerpt. -Editor

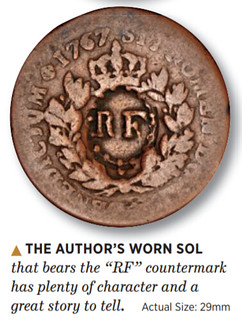

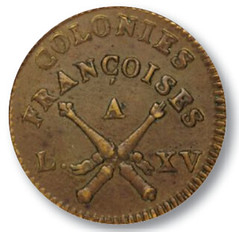

Among the coins listed as “Colonial Issues” in R.S. Yeoman's Guide Book of United States Coins (the “Red Book”) is a 1767 piece struck for France's colonies by the Paris Mint. Usually found with an oval counterstamp bearing the letters “RF,” it is an interesting coin for several reasons. Much more can be said about it than is mentioned in the Red Book, which states simply that the piece was made for use in the French colonies and unofficially circulated in Louisiana, along with a variety of other coins and tokens. This copper sol (equal to 12 deniers and later called a sou) was roughly comparable to a U.S. large cent in purchasing power. Sol Story The sol originally was issued in 1767 to replace old billon coin - age (which contained a copper/ silver alloy with less than 50- percent silver) that circulated in various French colonies, including several Caribbean islands. With a weight of 12.2g and a diameter of 29mm, the sol was roughly the size of a U.S. large cent. The obverse shows crossed scepters, representing justice and French sovereignty. The legend COLONIES FRANÇOISES L(UDO VI CUS) XV indicates the piece was produced for the French colonies of King Louis XV. The reverse bears three fleur de lis within a crowned wreath and the date 1767. The surrounding Latin legend SIT NOMEN DOMINI BENEDICTUM translates “Blessed is the Name of the Lord.” Surviving documentation suggests that only a fraction of the 1.6 million sols minted were issued at that time. In 1767 citizens of the colony of Guadeloupe rejected the issue, and it did not circulate.

No doubt some sols found their way to New Orleans, along with a variety of other Caribbean coinage, but they never were officially authorized for use there or intentionally imported in large quantities. A number of them might have been brought in by travelers and sailors, but the same could be said for almost any coin that circulated in the Caribbean, such as a 1740 skilling of the Danish West Indies or a countermarked coin of Martinique. Louisiana was not a French territory in 1767 nor in 1793, when these coins were issued. No part of Canada was French during their use (except for the tiny islands of Saint Pierre and Miquelon, which are French to this day). In a U.S. colonial collection, it would be far more justifiable to incorporate British half pence, Spanish silver, half joes (Brazilian 6,400 reis) and other coins common in the colonies and early states rather than this 12 deniers. Sadly, although the sol is an interesting coin with a fascinating history, its status as a U.S. colonial issue is no more justified than many other circulating European coins of its day. However, that does not detract from its appeal. For more information about the American Numismatic Association, see: Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|