PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

IN OTHER NEWS: JULY 1, 2018Here are some additional items I came across in the media this week that may be of interest. -Editor

Attic Finds Although few and far between, there are still good "attic finds" to be had. Nothing numismatic here, but this article

from Sotheby's provides hope for all collectors. -Editor

The vase was discovered by chance in the attic of a French family home and brought into the Paris office by its unsuspecting owners in a shoe box. Over the years there have been a number of remarkable stories about people who’ve made startling discoveries in the least likely of places and we decided to take a look at a few to coincide with our online-only Attic Sale: Offered Without Reserve, which is open for bidding until 29 June... In 1991 the first half of the original text of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, with handwritten notes by the author Mark Twain, was discovered in a trunk in a Los Angeles attic. Paul Needham, who headed up the Sotheby’s books and manuscripts department at the time said of the discovery: "This is the most amazing survival imaginable so far as American literature is concerned. The only thing comparable to it I can think of would be an original Shakespeare manuscript." To read the complete article, see: Pros and Cons of Stealing Fine Art Easy to steal, impossible to sell. This Bloomberg article discusses the good, bad and worse news for anyone tempted to steal

fine art. -Editor

And that leads us to the only real solution for thieves: steal something you can turn into something else, like the gold coin in Berlin. Charney cites the 2004 theft of a bronze sculpture by Henry Moore, valued at about 3 million pounds ($3.98 million). The sculpture weighed about two tons, “and it was almost certainly chopped up and melted down, then converted to ball bearings,” Charney says. Hertfordshire police determined it was cut up on the night of the heist, moved through various scrap dealers, and shipped abroad. The raw material was worth just about 1,500 pounds. In the case of the Berlin coin theft, the thieves were in a similar position with a much more valuable commodity than bronze. Police suspect that the group melted the coin down and sold the gold for hundreds of thousands of dollars. “Of course, that’s a fraction of its intact cultural value,” Charney says. “There’s almost never been a criminal who knew about, or cared about, art.” To read the complete article, see: Why Medieval Monasteries Branded Their Books For bibliophiles, here's an article on why medieval monasteries branded their books -Editor

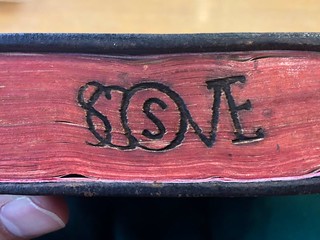

In particular, texts tagged along as missionaries fanned out to proselytize across the New World. When it came to converting indigenous people to Christianity, religious texts were a powerful weapon in missionaries’ arsenals, and psalms, confessions, and other liturgical texts—written in Spanish, Latin, and scores of indigenous languages—were printed in Europe and shipped across the ocean to New Spain. This land, encompassing present-day Mexico and other portions of Central and South America, was an epicenter of conversion efforts, and it soon became a hub for the printed word, too. It’s easy to imagine how books could become casualties of a life that was itinerant by design. “Missionaries’ whole mission was to go out and constantly be on the move, and the books were, as well,” says Melissa Moreton, an instructor at the Center for the Book at the University of Iowa. Before they did, monasteries and convents often made a bold claim to ownership. With a scalding tool, they seared distinctive marks onto the pages. To read the complete article, see: Julian Star on Caesar Augustus Denarius This June 29, 2018 Coin World article by Jeff Stark discusses an interesting silver denarius of Caesar Augustus. See the

complete article online for more. -Editor

A famous celestial event of antiquity was recorded on an ancient coin. A silver denarius of Augustus (also known as Caesar Augustus), issued circa 19 to 18 B.C., depicts the so-called Julian star. The reverse of the coin shows the “Julian Star,” a bright comet that appeared in the heavens during the summer of 44 B.C., a few months after the assassination of Julius Caesar (March 15, 44 B.C.). To read the complete article, see:  Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|