PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

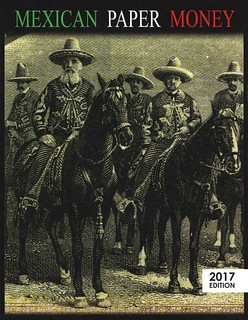

BOOK REVIEW: MEXICAN PAPER MONEY 2017 EDITIONPablo Hoffman submitted this review of Mexican Paper Money, 2nd edition. Thank you! -Editor edited by Corey Frampton, Duane Douglas, Alberto Hidalgo & Elmer Powell. World Numismatics, LLC, PO Box 5270, Carefree, AZ 85377. Available only as digital download from worldnumismatics.com. Price $35. IBNS #224 (1960s) /#10676 (2012) The human species enjoys peace, yet seems to irresistibly pursue conflict. We interminably wage invasion, war, and conquest through subjugation of others. Those others, not unexpectedly, often resist. Such conflict has been a persistent, defining force in Mexico during its 10,000 years of evolution. The wide horizons and profound resonances of Mexican paper money, just as any deep comprehension of the vast panorama of Mexican history, cannot be grasped except against the backdrop of these dramatic and often violent events. The Aztecs dominated their era, exacting tribute from their subjugated neighbors in material goods, slaves, and sacrificial human offerings to the gods as inked in the ancient codices on amatl (paper made from the bark of the fig tree). The victory of the conquistadores simply brought more of the same, summoning brutal dominance and new gods, substituting the fanatic dogma of Spanish Catholicism and the Spanish Inquisition for the ancient Aztec deities. Three of the last five centuries of Mexico’s existence were under the iron hand of Spanish colonial despotism. The indigenous people struggled for their independence against the stranglehold of their Iberian overlords. Whether the slash of obsidian-blade macuahuitl cudgels wielded by Aztec warriors bedecked as eagles and jaguars, or the rumbling of post-Conquest cannons pounding like hoofbeats of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, war, famine, death, and disease were frequent invaders into nearly all the land.

Little or none of the traditional Spanish colonial coinage of gold doblones and silver reales was available to the public, so out of dire necessity the people did what they always do: they improvised. Defying vice-regal prohibitions, illegal vest-pocket and back-room mints popped up. Chimneys erupted smoke, crucibles poured out liquid metal, anvils rang under hammer blows. Crude dies to cast or stamp devices and denominations were painstakingly, clandestinely designed. People invented what they needed, and what they needed was money. If it wasn’t as elegantly designed or finely produced as the old Spanish pillar dollars and pieces-of-eight, or the later republican coinage, no matter. Employers and employees, ranchos and ranch-hands, businesses and clients, sellers and buyers, all made do with the motley quasi-currency, and carried on. What they made do with was an unofficial medium of exchange consisting largely of a vast variety of tokens, often in limited local circulation, usually coined in copper or bronze. People had no option but to accept them, calling them pilones, tlacos, fichas, or fichas de hacienda. But a new problem quickly arose: they ran out of copper. Again, they improvised. They manufactured the fichas out of other metals at hand; they melted down and alloyed brass, iron, white metal, lead. When metal disappeared, they used wood, leather, bone, even glass, and then even the unthinkable: paper!

Exactly 100 years after the first war for independence, revolution erupted in 1910 and during the entire second decade of the 20th century violence rampaged throughout the country. Not until mid-century did a well-organized and administered polity finally coalesce and function and earn recognition as a modern nation-state. Every step of the way, paper money chronicled and depicted the events and people of the moment. From the picturesque vignettes on the note issues of the 19th Century bancos, to the 20-plus ton Aztec Stone of the Sun, in an exquisitely engraved image centered on the 1936 1-peso note, to Miguel Hidalgo in a dynamic gesture on a current 200-peso note commemorating the War of Independence at its bicentennial, Mexico is outstanding in the ubiquitous use of its circulating paper currency as a medium to display its history. The notes picture tribal rulers, indigenous, mestizo, and criollo leaders both men and women, battles, treaties, gems of architecture and art, industries and occupations, cultural and historical artifacts, and much more.

These spacious dimensions of the entire saga of Mexico are displayed in the sweeping iconographic panorama of its paper money. The details are the focus of this second edition, aided and abetted by more than forty contributors. This book has been previously reviewed in glowing terms by knowledgeable numismatists, and deservedly so. Its content, structure, scope, and numbering protocol have been perused and analyzed and amply commented on by other reviewers. We see notes of the early eras, of the empires, and of the republican periods. There are sections segregated by states and municipalities, the bancos, the military, private issues, pre-Revolution, Revolution, and post-Revolution, ending in the 1970s with the American Bank Note Company issues of the modern Banco de Mexico. This second edition is encyclopedic in coverage of types and yet goes deep in detailing varieties. Building on the printed 2010 first edition, categories are amplified, date and series tables are extended. Prices are adjusted, generally upward, sometimes radically so. New discoveries are added to this kaleidoscope of paper money and each is a new thrill for the enthusiast. This 2nd edition is the indispensable reference work on the subject. For more information, or to order, see: To read the earlier E-Sylum article, see: Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|