PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

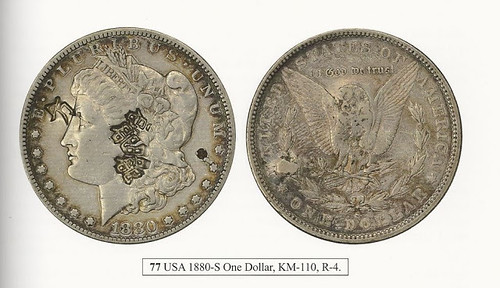

THE CAMERON HOUSE THEORYI was pleased to discover that economics blogger JP Koning had referenced a recent E-Sylum item about Civil War redenominated U.S. coinage. That was my favorite article from that issue, which had a number of strong candidates. Thanks again to Bill Groom and Bob Merchant for their contributions. It's great to see our efforts fueling further discussion and research. Here's an excerpt from JP's blog post, which includes his earlier tweet of our image. -Editor The idea that coins circulated at more than their precious metals content, or intrinsic value, can be found throughout Mitchell-Innes's two essays. He uses the existence of this premium as proof that the metal content of a coin is not relevant to its value, its credit value being the sole remaining explanation. To some extent, I agree with Mitchell-Innes. Over the course of history coins have often circulated above their intrinsic value, and from time-to-time this premium has been due to their value as credit. The merchants' counterstamps below are great examples. By adding a stamp to a government coin, these merchants have elevated the coin's value from one cent to five or ten cents.  These three coins are straight out of Mitchell-Innes two essays. As I say in the tweet, counterstamped coins effectively functioned as an IOU of the merchant. For instance, take the five cent Cameron House token, on the right. This token was issued by a Pennsylvania-based hotel—Cameron House. Its intrinsic value was one cent, but Cameron House's owner promised to take the coin back at five cents, presumably in payment for a room. The sole driver of the coin's value was the reliability of Cameron House's promise, the amount of metal in the token having no bearing whatsoever on its purchasing power. While Cameron House's stamp turned metal into a much more valuable form of credit, not all stamps do this. Last week I wrote about coin regulators who regulated gold coins and shroffs who chopped coins. Both functioned as assayers, weighing a coin and determining its fineness. If the coin was up to standard, the regulator or shroff stamped their brand onto its face and pushed it back into circulation. Below is a chopmarked U.S. trade dollar:  Actually, this is of course a regular U.S. Morgan silver dollar, not a Trade Dollar. But the reasoning is valid nonetheless. -Editor But unlike the Cameron House stamp, the regulation or chopping of coins didn't turn them into a credit of the regulator or shroff. The marks were simply indicators that the coin had been audited and had passed the test, and nothing more. Both the Cameron House coin and the chopped U.S. trade dollar would have traded at a premium to the intrinsic value of the metal that each contained. But for different reasons. As I wrote above, the Cameron House coin was a form of credit, like a paper IOU, and thus its value derived from Cameron House's credit quality, not the material in the token. But not so the chopped U.S. trade dollar. Precious metals are always more useful in assayed form than as raw bullion. While it is simple to test the weight of a quantity of precious metals, it is much harder to verify its fineness. This is why chopmarks would have been helpful. Anyone coming into possession of the chopmarked coin could be sure that its fineness had been validated by an expert shroff. And thus it was more trustworthy than silver that had no chopmark. People would have been willing to pay a bit extra, a premium, for this guarantee. Remember that a decline in the amount of metal in a five-cent Cameron House token would not have changed its purchasing power. With a chopmarked trade dollar, however, any reduction in its metal content flowed through directly to its exchange value. This is because a chopmarked dollar was nothing more than verified raw silver. And just as the value of raw gold or silver is determined by how many grams are being exchanged, the same goes for a chopmarked trade dollar. And so whereas Mitchell-Innes has a single theory of money, we've arrived at two reasons for why coins might trade at a premium to intrinsic value, and why their purchasing power might change over time. The Cameron House theory, which also happens to be Mitchell-Innes's theory, and the chopmarked trade dollar theory, which is completely contrary to Mitchell-Innes's essays. I've used private coinage for my examples, but these principles apply just as well to government coinage. Our modern government-issued coins are very similar to the Cameron House tokens. They are a type of IOU (as I wrote here). In the same way that trimming away 10% from the edge of a $5 note won't reduce that note's purchasing power one bit, clipping some of the metal off of a toonie (a $2 Canadian coin) won't alter its market value. The metal content of a modern coin is (almost always) irrelevant. But whereas modern government coins operate on Cameron House principals, medieval government coins operated on the same principals as chopmarked traded dollars. In England, a merchant who wanted coins would bring raw gold or silver to a mint to be converted into coin. But the merchant had to pay the mint master a fee. The amount by which a coin's market value exceeded its intrinsic value depended on the size of the mint's fee. Say it was possible for a merchant to purchase a certain amount of raw gold with gold coins, pay the fee to have the raw gold minted into coins, and end up with more coins than he started with. This would be a risk-free way to make money. Everyone would replicate this transaction—buying raw gold with coins and converting it back into coins—until the gap between the market price of a coin and the market price of an equivalent amount of gold had narrowed to the size of the fee. Premia on coins weren't always directly related to mintage fees. English mints usually operated on the principle of free coinage—anyone could bring their gold or silver to the mint to be turned into coin. But sometimes the mint would close to new business. Due to their usefulness and growing scarcity, gold coins would circulate at an ever larger premium to an equivalent amount of raw gold. Since merchants could no longer bring raw gold to the mint and thereby increase the supply of coins, there was no mechanism for reducing this premium. So as you can see, whether the mint was open and coinage free, or whether it was closed, the premium had nothing to do with the coin's status as a form of credit. It was due to a combination of the superiority of gold in validated form and the availability of validated supply. In sum, Mitchell-Innes is certainly right that coins have often been a form of credit. A stamp on a piece of metal often elevates it from being a mere commodity to a token of indebtedness. In which case we get Cameron House money. But as often as not, that stamp is little more than an assay mark, a guarantee of fineness. In which case we have chopmarked trade dollars. Both sorts of stamps put a premium on the coin, but for different reasons. To read the complete article, see: To read the earlier E-Sylum article, see:  Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|