PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

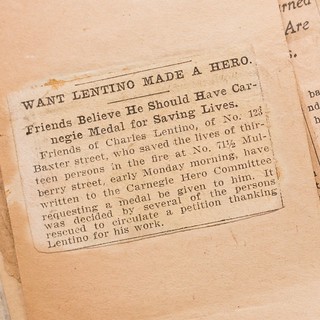

A VISIT TO THE CARNEGIE HERO FUND COMMISSIONGeorge Cuhaj forwarded this New York Times article on Carnegie Hero medals and the Commission that awards them. Thanks! -Editor  ... a person expiring between the ages of one and 44 years is more likely to fall under what the charts render a yawning wedge of bilious turquoise: the color of dying by accident. What cannot be gleaned from such charts are accidents that are thwarted — or the names of the people who attempted to thwart them. Acknowledging them is the self-appointed task of the Carnegie Hero Fund Commission: a private foundation that identifies and rewards members of the public for being heroes. Year-round, a small team of office workers endeavors to analyze the seconds when somebody intervenes to try to prevent death or serious injury. From a tidy headquarters in downtown Pittsburgh, they laboriously collect and scrutinize newspaper stories, hospital records, fire marshal reports, witness statements, family interviews, location sketches, tide charts, photographs of charred clothing, stairway dimensions, expert testimony on seasonal bear activity — anything they can get their hands on to better understand those calamitous situations in which outsiders intervened. The Hero Fund’s task is not to assign blame, nor to explain why something happened. It is to identify those mere mortals who attempted individually, and bodily, to disrupt the relentless course of fate. And to send them a check for $5,500 and a hand-struck medal on behalf of humankind. The paychecks for those who do this work arrive courtesy of a man who died 100 years ago. It is a testament to the magical ability of money to become more money that Andrew Carnegie’s gift of $5 million in 1904 has enabled the Carnegie Hero Fund Commission to distribute $41.3 million — and 10,135 medals — to individual heroes over the last 115 years. Hero Prerequisites

The award is open to civilians only; soldiers cannot win, nor can rescue professionals unless they have acted far outside the scope of their usual duties. (For instance: An off-duty firefighter recovering from shoulder surgery in British Columbia in 1997, recognized for her efforts to drive off a bear as it mauled a man to death, was Hero #8281). Individuals previously convicted of crimes are eligible. (“Heroes deserve pardon and a fresh start,” the official 1904 deed of trust declares.) Hero #5969 received his award for a split-second decision to launch his body at an active shooter in Michigan in 1970. At the time, both shooter and hero were being transferred between prison facilities in the back of a police sedan; the hero was still shackled. Many, many heroes have been awarded for tackling armed gunmen. They include a street cleaning commissioner, a human resources director, an exotic dancer, several teachers, a data analyst, a barber, a telemarketer, a newspaper editor, a bricklayer, an investment adviser, and a county jail elevator operator whose parents were born enslaved. To separate the wheat of true heroism from the chaff of acts that are merely extremely admirable, the fund requires “conclusive evidence to support the act’s occurrence.” The gathering of such evidence falls to a team of four investigators. Human and animal attack cases typically get the most attention when Carnegie awards are announced every quarter, said Eric Zahren, the fund’s president. “It just affects the psyche a little bit differently than natural perils like drowning, burning.” Before he became president, Mr. Zahren spent 25 years in the Secret Service, retiring as the special agent in charge of the Pittsburgh field office. “In my last career, I dealt a lot with the darker side of human nature,” he said. Even the bleakest Carnegie stories, by contrast, strobe with flashes of good will. Inherent in every heroic attempt is hope. Many heroes escape not just with their own lives, but having rescued someone else. I had the pleasure of visiting the Carnegie Hero Fund Commission offices in Pittsburgh in preparation for the 2004 ANA World's Fair of Money. As the show's Chairman I helped organize a special exhibit of the Carnegie Hero medals and became a collector of them myself. Each one has an amazing story to tell. -Editor To read the complete article, see:

Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|