PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

YELLOW FEVER AT THE U.S. MINTThis article from The Conversation examines how the U.S. Mint paid and retained its workforce during the 1793 work stoppage caused by the yellow fever pandemic. -Editor Fever pains in the early republic

For the next decade, yellow fever erupted sporadically in Philadelphia and other populous coastal cities and towns. The outbreaks shut down businesses, suspended court sessions, and drove residents to flee. During the first outbreak of 1793, a flour miller summed up the experience with these words: "I want to be doing something, but the Fever in Philadelphia has thrown us all out of our Geers." The pandemic forced Americans to tackle some of the questions that have surfaced in the past week: Would some people risk exposure to the virus in order to earn wages? Should employers allow workers to stay away from their jobs because of the risk of infection? How would families who relied on daily or weekly wages pull through? Neither state nor federal lawmakers tried to answer these questions in the 1790s. But federal agencies had to respond as employers. The United States Mint, which produced the young nation’s coinage, devised the most effective response. Protecting workers in a pandemic

A copper penny produced in 1793 by workers at the U.S. Mint in Philadelphia. This policy became the Mint’s standard response to yellow fever and was applied six times over eight years. Most workers received their pay after the outbreak, but highly skilled workers at the rank of officer could obtain their full quarterly pay in advance. Then, as now, the financial pains of a pandemic did not hit all classes equally. The U.S. Mint’s response to yellow fever struck a balance between workers’ and employers’ needs. Workers put on furlough were guaranteed jobs when the public health crisis was over. Meanwhile, the Mint secured their loyalty by promising back pay, so it was able to resume operations quickly after each outbreak. Today, once again, business leaders and politicians are compelled to respond to a pandemic. State and federal legislators are taking bold steps to counter anxiety with assurances of stability. And they are developing new safety nets for workers made vulnerable by the coronavirus. As lawmakers consider their options, there are lessons to be found in U.S. history about sustaining workers during a public health crisis. The Conversation is an independent and not-for-profit news organization. They reach out to leading scholars across academia for unbiased insight on news of the day. Consider signing up for their daily email newsletter or making a donation to help fund independent journalism. -Editor To read the complete article, see:

To sign up for The Conversation newsletter, see:

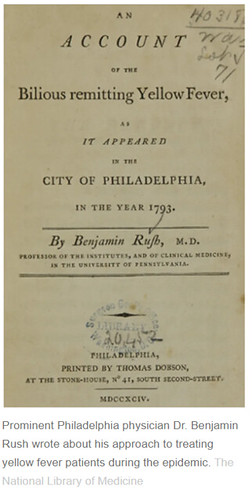

Dave Bowers also wrote on this topic for his Coin Update blog. -Editor Turn on the television or check the news on the Internet and 90% of the coverage seems to be about the coronavirus pandemic. Events, including coin shows, have been canceled left and right. Self-isolation is being practiced across the land. Meanwhile, coin auctions and other commerce is continuing without problems, thanks to the Internet. The Stack’s Bowers Galleries sale of a few days ago was very strong as people were able to participate online. I have not heard of any problems with coins in holders or with books, and feel that it is easy enough to wipe the surface of anything you get from an outside source. As of this writing, the four mints in the United States are still open. History tells us that over 200 years ago yellow fever epidemics in Philadelphia forced the closing of the Mint on occasion. Yellow fever was rampant in the late summer of 1793, and Joseph Wright, a distinguished engraver who prepared certain pattern coins in 1792 and the Liberty Cap cent of 1793, was among those taken by it. In 1797 the fever struck again, forcing many people in Philadelphia to go to the countryside. The Mint closed in late August and did not reopen until the end of November. In 1798, and again in 1799, the dreaded yellow fever epidemic struck the Philadelphia area in all its fury. People fled for their lives, but even though the Mint was closed for several months in each of these years, coinage resumed soon after reopening with a minimum of trouble. In 1803, the fever struck again and the Mint was closed for six weeks. Indeed, a lengthy essay could be written on the fever and coinage. To read the complete article, see:

Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|