PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

ASSAY COMMISSION MEDALSSteve Roach published a Coin World article May 30, 2020 about a great series of U.S. Mint medals - the Assay Commission medals. Here's an excerpt. -Editor

The United States Assay Commission no longer exists, but is remembered by a series of medals designed by many of the U.S. Mint's top talents in the 19th and 20th centuries. The commission's purpose was to supervise annual testing of gold, silver, and other metals in the Mint's coins to make sure that they were struck in accordance with specifications. Members, among them many collectors, received a specially designed medal for their participation. The final medal in 1977 was sold to the public. A number of these medals were offered in the Stack's Bowers Galleries March 18 auction of the Richard Jewell Collection.

To read the complete article, see:

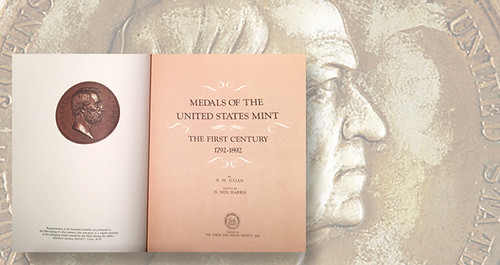

The article linked to a nice 2016 Coin World article by Joel Orosz on the R.W. Julian book Medals of the United States Mint: The First Century, 1792-1892. -Editor

He divides all the medals produced by the U.S. Mint in its first century into 14 classes, starting with those made for the members of the annual Assay Commission, ending with Religious and Fraternal Medals, and covering topics such as Indian Peace Medals and Life Saving Medals in between. Julian illustrates and describes each medal, obverse and reverse; gives each a discrete catalog number; identifies its engraver; lists its size and composition (gold, silver, bronze); provides a brief history; and reveals if the original dies still repose at the Mint (making restrikes a possibility). All of this is invaluable to the researcher and collector, but the most fascinating parts of the book occur when Julian exposes the ample dirty laundry that always accumulated at the 19th century Mint. Consider the fiasco surrounding MI-19, the Military gold medal honoring Brig. Gen. Eleazer Ripley's heroics during the War of 1812. Congress authorized the medal on Nov. 3, 1814. The Mint took almost 24 years to strike it! Julian recounts the entire comedy of errors, starting with the Mint's foot-dragging (not until 1821 did engraver Moritz Furst prepare the reverse). Ripley added to the problem by stubbornly refusing, for five long years, to provide his own portrait for the obverse. Then accusations that Ripley hadn't participated in the battles mentioned on the reverse stalled progress for years until proven false. Finally, Chief Coiner Adam Eckfeldt had to pay for the gold used to strike Ripley's medal out of his own pocket, so it wasn't until 1838 — only a year before he died — that Ripley at last received his tribute, and Eckfeldt got reimbursed (through a special act of Congress)! That is just one case; a whole series of stories documents the personal profiteering of Eckfeldt's successor, Franklin Peale, who pocketed proceeds from medals made by Mint employees, on Mint time, with Mint material, using Mint presses.

To read the complete article, see:

Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|