PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

THE HISTORY OF THE FREEDMAN'S BANKA publication of the University of Chicago Booth School of Business looks at the history of The Freedman's Bank -Editor

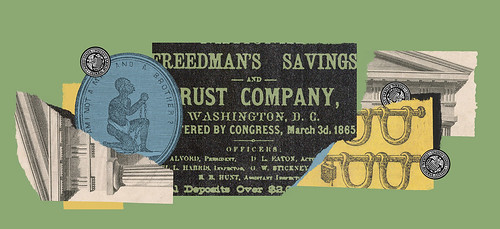

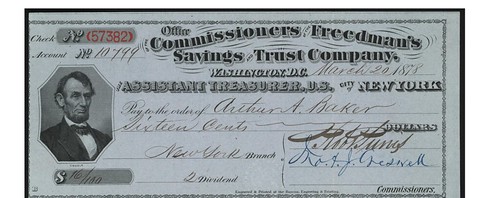

Some of the research into the Freedman's Bank stems from a visit by Chicago Booth's Constantine Yannelis to the US Treasury in fall 2018. Due to a temporary security issue, the main entrance was closed, and Yannelis was routed to exit the building via an annex that two years earlier had been renamed "The Freedman's Bank Building." Having never heard of the bank, Yannelis looked it up. The first Freedman's Bank opened on April 4, 1865. As University of California at Irvine's Mehrsa Baradaran explains in her 2017 book The Color of Money: Black Banks and the Racial Wealth Gap, the government originally proposed distributing land to people who had been enslaved, but faced a violent backlash from Southern whites. "Instead of land, freed slaves got rights that they could not use due to their economic and political status at the bottom rung of society. They also got a savings bank, which was another form of diversion that would be repeated in the next century," Baradaran writes. Black Americans still opened accounts with the Freedman's Bank at a "phenomenal" rate, according to the US National Archives and Records Administration. Customers, almost entirely newly freed Black Americans, could open an account with as little as 5 cents, and interest was paid on deposits of $1 or more. Most deposits were small, less than $60 on average. More than 100,000 people became customers—farmers, cooks, barbers, nurses, carpenters—many of them likely taking home their first paychecks. Stein and Yannelis analyzed surviving account-register records that had been microfilmed by the National Archives and later digitized in CD-ROM format by FamilySearch, a nonprofit genealogy association, obtaining data from 107,197 accounts across 27 Freedman's Bank branches, totaling 483,082 nonunique individuals—roughly 12 percent of the 1870 Black population in the American South. They lined these records up with a sample from the 1870 census containing information on schooling, literacy, employment, and wealth among Black Americans. (Literacy data was collected by the Census Bureau at the time.) The Freedman's Bank, they determine, had a small but significant impact on the economic well-being and outlook of its account holders. An initial regression analysis finds that individuals in households with an account at the bank were 1 percentage point more likely to be literate and to attend schools. The same individuals were 2 percentage points more likely to work and to have higher incomes than their peers. Being able to bank raised incomes, literacy levels, and landownership through one or more channels, according to the research. Among these, having an account may have allowed individuals to save to make large purchases, such as a plot of land; to invest in workers; or to open a business. It also may have helped them overcome challenges associated with irregular income and shocks, which were often tied to fickle agricultural harvests, by providing a place to make consistent, recurring payments and save up a cash cushion. (Costs associated with withdrawals may have discouraged depositors from taking out money unless necessary, which encouraged saving.) Southern Democrats were generally hostile to the bank, its customers, and its supporters. Meanwhile, Republicans, who had set up the bank, were overall more supportive of programs such as schools and economic development. The access to financial services that the Freedman's Bank was able to offer to an unbanked population had real impact at the Black American individual and household level, they argue, and this impact extended to the community in terms of its ability to accelerate education and wealth accumulation. An average county near an early bank branch had about 10,700 Black residents and 2,700 account holders, and the analysis suggests financial inclusion boosted school attendance rates by up to 5 percentage points and literacy by up to 18 percentage points, with positive effects on income, employment, and business ownership. The Freedman's Bank was not to last, however. Although set up as an institution strictly dedicated to savings, the bank was soon investing its depositors' hard-earned savings into risky railroad companies and real estate. Its coffers were largely co-opted by the First National Bank, which offloaded its liabilities onto the Freedman's Bank books with no objection from the latter's all-white trustees. The Panic of 1873 was a death knell, as real-estate prices fell, loans went bad, and depositors demanded their money back. Social reformer, author, lecturer, and statesman Frederick Douglass was elected the bank's president in a bid to save it, but he quickly became aware of the bank's dire conditions and turned to Congress. On June 29, 1874, the bank's trustees voted to shutter it and left more than 60,000 depositors with nearly $3 million in losses. Federal deposit insurance did not yet exist, and while there was some compensation for customers, the fight to make depositors whole continued in Congress for decades, into the 20th century, to no avail. The Freedman's Bank headquarters was torn down in 1899, replaced in 1919 by what would become the Treasury annex.

To read the complete article, see:

It's a sad and disappointing history for what could have been an important financial institution well into the 20th century or beyond. See John Kraljevich's article on NNP (the last of those linked below) for more. -Editor

For more information, see:

Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|