PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

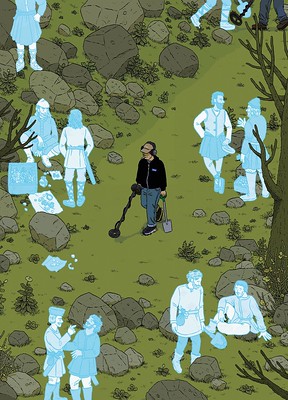

THE CURSE OF THE BURIED TREASUREThis November 9, 2020 New Yorker article examines the fate of two metal-detector enthusiasts discovered a Viking hoard. -Editor

Coins of Ceolwulf II, of Mercia, and Alfred, of Wessex For much of the early Middle Ages, Mercia was the most powerful of the four main Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, the others being Wessex, East Anglia, and Northumberland. In the tenth century, these realms were unified to become the Kingdom of England. Although the region surrounding Leominster (pronounced "Lemster") is no longer officially known as Mercia, this legacy is preserved in the name of the local constabulary: the West Mercia Police. On June 2, 2015, two metal-detector hobbyists aware of the area's heritage, George Powell and Layton Davies, drove ninety minutes north of their homes, in South Wales, to the hamlet of Eye, about four miles outside Leominster. The farmland there is picturesque: narrow, hedgerow-lined lanes wend among pastures dotted with spreading trees and undulating crop fields. Powell, a warehouse worker in his early thirties, and Davies, a school custodian a dozen years older, were experienced "detectorists." There are approximately twenty thousand such enthusiasts in England and Wales, and usually they find only mundane detritus: a corroded button that popped off a jacket in the eighteen-hundreds, a bolt that fell off a tractor a dozen years ago. But some detectorists make discoveries that are immensely valuable, both to collectors of antiquities and to historians, for whom a single buried coin can help illuminate the past.

Although the Vikings did not use coins as a form of currency, they had a bullion economy-the trading of metals, based on weight and purity-and appreciated coins as portable forms of wealth. They coveted silver, which was not mined in their own lands; gold was even more prized. To obtain these precious metals, the Vikings stole or requisitioned the contents of Anglo-Saxon monastery vaults, which often included finely worked silver or gold, and chopped them into pieces, for purposes of trade-archeologists call such fragments hacksilver or hackgold-or melted them into ingots, for ease of weighing. A Viking hoard typically contains these forms of metal, and also coins minted by the Anglo-Saxon kings whose lands they had invaded.

Missteps from the very beginning of their adventure ensured an unhappy ending to the story. Proper protocols were not followed. -Editor Gareth Williams, the curator of early-medieval coinage and Viking collections at the British Museum, became entranced by the Norse world as a small child, while paging through a library book. His grandmother, encouraging his passion, made him a helmet and a shield out of cardboard. He went on to study medieval history at the University of St. Andrews, in Scotland, where he completed his Ph.D., and then joined the British Museum. In the summer of 2015, he was approached by a contact in the coin trade. As Williams told me recently, the contact informed him that several pieces of what appeared to be a Viking hoard were being offered to dealers. Some of the coins were Two Emperors, a type so rare that numismatists knew of only two extant examples: one was discovered in 1840, the other in 1950. A Two Emperor coin had never appeared on the open market, and a single one was valued at a hundred thousand dollars. A hoard with a substantial number of rare coins could be worth more than ten million dollars. The fact that individual coins were being offered to dealers suggested that the hoard was in danger of being broken up and vanishing onto the black market. According to Williams, the contact told him that he hadn't personally seen the coins but "understood immediately from the description that this must be undeclared treasure."

It's a fascinating and well-written tale that any numismatist should appreciate. See the complete article online. The hoard had an estimated value of "anywhere between four million and fifteen million dollars" and the finders are facing jail sentences. -Editor

To read the complete article, see:

THE BOOK BAZARREWayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|