PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

THE FAROUK 1933 DOUBLE EAGLE, PART 2With permission, here's an excerpt from the very detailed history description of the Farouk 1933 Double Eagle up for auction in Sotheby's June New York sale. Thanks. -Editor THE BRIEF LIFE AND DEATH OF AMERICA'S LAST GOLD COIN The Factory on Spring Garden Street As citizens lined up to return their gold at Federal reserve banks, the employees within the massive neoclassical edifice of the Philadelphia Mint saw little action. Both the Cashier's and Coining Departments' daily records reflect this torpor. In that beleaguered, depressed economy there was little need to make new money; the entire 1933 production at the Philadelphia Mint approximated a single day's output in 1928. Each step of production and delivery was carefully choreographed and scrupulously recorded. On Thursday, March 2, the first 1933 Double Eagles were struck, but it was not until March 15, 1933 that the requisite number (25,000) passed quality control when the first delivery to the Cashier was made. The delivery from coiner to cashier, as responsibility passed from one entity of the mint to another, was memorialized in manifold ways on multiple documents. Two examples were sent to Washington, D.C., for Special Assay to ensure quality, and an additional one coin from every thousand delivered was sealed in an envelope and deposited in a double-locked wooden box which would be opened at the Annual Assay the following February. At the close of March 15, the Cashier recorded in his Daily Settlement the remaining number of 1933 Double Eagles in his custody: $495,000 in the basement vault, and $4,460 (223 pieces) in an office safe. The gross amount received, less those reserved for assay, was recorded on the official Cashier's Daily Statement and sent to Mint headquarters. A total of ten deliveries (445,500 pieces), similarly recorded, were made, the last on May 19; in June the vast majority of 1933 Double Eagles was placed in Cage 1 of the massive Vault F—dead storage.

On January 30, 1934, with the government's vaults replenished by hundreds of millions of dollars in recalled gold, the Gold Reserve Act of 1934 was passed and Two weeks later, the last gold coins ever struck for circulation by the United States, the 1933 Double Eagles, were tested by the Annual Assay Commission. This newsworthy event marked the last testing of gold coins and the first Assay Commission presided over by a woman, Nellie Tayloe Ross.14 Nine Double Eagles were destroyed, and the remainder were noted by the cashier as received on February 20, 1934. In August 1934, Mint Director Ross ordered the melting of all gold coins held by the government—the 1933 Double Eagles awaited destruction. In October, she ordered that two examples be sent to the Smithsonian, the only institution or private collection that would ever be permitted to own an example of these historic coins — legally. But not the only one that wanted one.

TO HAVE NOT– AND HAVE

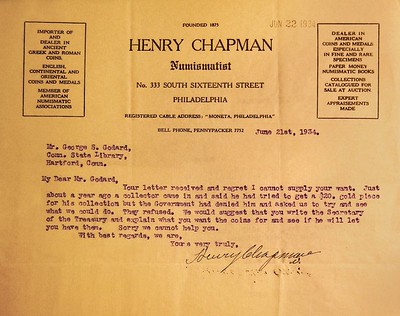

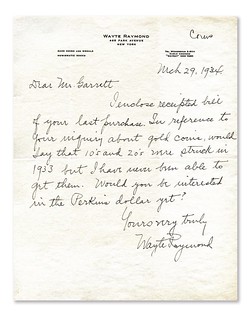

JUNE 1934 LETTER FROM PHILADELPHIA COIN DEALER HENRY CHAPMAN TO CONNECTICUT STATE LIBRARIAN GEORGE GODARD, INDICATING HE HAD BEEN UNABLE TO GET 1933 DOUBLE EAGLES IN 1933. (CREDIT: CONNECTICUT STATE LIBRARY ARCHIVES) In 1911 the State of Connecticut was bequeathed a stellar collection of coins, with the stipulation that examples of current United States coins be added annually. This responsibility fell to State Librarian George Godard, whose requests to the Mint and Treasurer's Office were honored for two decades. But not in 1933.

Connecticut's initial request for examples of 1933 Double Eagles was rejected, and on August 14 an appeal was subsequently turned down by Assistant Secretary of the Treasury Thomas Hewes, who wrote:

Similarly, the American Numismatic Society regularly purchased new coinage for its collection. Its relationship to the Mint and Treasury Department could not have been closer: Treasury Secretary Woodin, a learned coin collector, was a Board member; when in 1932 the ANS curator Howland Wood wrote to the Mint complaining about the quality of a Double Eagle just purchased, the mint director personally selected its replacement; and in January 1934, as new laws concerning gold coin ownership were being written, the ANS helped officials craft the language. But when the Society tried to obtain a 1933 Double Eagle it failed—repeatedly.

The correspondence, beginning April 28, 1933, includes a direct appeal to the Treasury Secretary from his friend ANS President Edward Newell, asking him

No one who tried to legally acquire a 1933 Double Eagle from the government could — ever. More next week. Meanwhile, give a listen to the CoinWeek podcast with David Tripp. -Editor

To listen to the podcast, see:

To read the complete lot description, see:

To read the earlier E-Sylum article, see:

Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|