PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

WHEN THE U.S. DEFAULTED ON ITS OBLIGATIONSThis Washington Post missed the cut for last week's issue and is no longer timely, but but it's a perennial topic that will come back in the news as early as December. -Editor Congressional fights over raising the debt limit often result in superlatives. A failure to raise the debt limit would almost certainly shake the financial markets unless, perhaps, it was only a brief, technical breach with a clear resolution in sight.

But one superlative that should be retired is

Some of these cases have been lost to mists of history, though one default was recently the subject of an interesting book titled

Some might argue these cases are not comparable to a failure to raise the debt limit — and many took place before the world economy was so interconnected. But they are all examples of when the U.S. government reneged on commitments it had made to investors. We were aided in our research by Alex J. Pollock, a former banker and Treasury official who is the author of

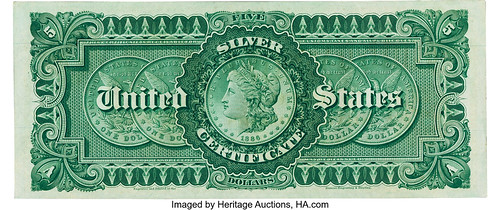

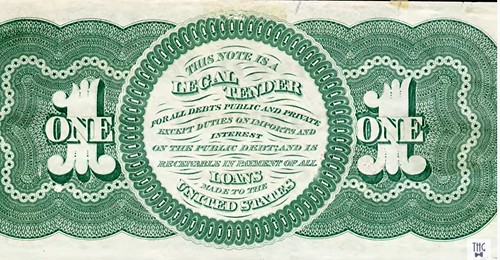

1862

So, Congress in 1862 abandoned the promise and declared the paper notes were legal tenure even though they were no longer backed by the equivalent in gold or silver. This is why U.S. currency to this day has the notation: I'ver got the Spaulding book in my library. The article goes on to discuss the 1933 gold order, the 1968 reversal on the redemdion of silver cerificates, and the 1971 closure of the Treasury gold window. -Editor

To read the complete article, see:

Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|