PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

1886 LATIN MONETARY UNION SILVER CROWNHere's a great article by Ursula Kampmann on a rare silver crown and its relation to the Morgan dollar. -Editor Gold, Silver, the Morgan Dollar and the Rarest Silver Crown of the Latin Monetary Union On 16 November 2021, Numismatica Genevensis will be auctioning a very important rarity: 5 francs, 1886 – the rarest silver crown of the Latin Monetary Union. Produced around the same time as the Morgan dollar, its rareness also shares the same economic and historical background: the overproduction of silver in the American town of Virginia City, Nevada.

By Ursula Kampmann

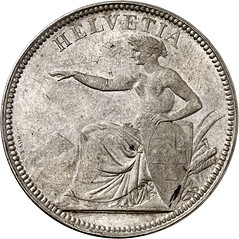

On 16 November 2021, Numismatica Genevensis will be auctioning a very important numismatic rarity. It is the rarest silver crown of the Latin Monetary Union. Only five specimens of this 5-franc coin from 1886 are known: three of them are located in Switzerland's most important museums. Only two of them are in private hands. And now, for the first time since 2008, one of those two specimens is coming onto the market. Swiss Confederation. 5 francs 1886 B, Bern. One of two specimens in private hands. One of five known specimens. From Auction SKA Bern 1 (1983), Lot 659. NGSA 5 (2008), Lot 1292. NGC MS64. FDC. Estimate: CHF 200,000. From Auction Numismatica Genevensis 14 (15 and 16 November 2021), Lot 395. The estimated price for this piece, graded as MS64 by NGC, is CHF 200,000. The obverse depicts Helvetia against the backdrop of the Alps, a die created by Geneva-born medallist Antoine Bovy for the new coinage of the recently established confederation. The incredibly rare year can be found on the reverse, surrounded by a wreath of oak leaves and Alpine roses. The coin was minted in Bern, hence the little B under the wreath. This coin not only holds significance in the world of Swiss numismatics. It is a key testament to the economic history of the 19 th century, bearing witness to the close link between the silver deposits discovered in the American state of Nevada and European monetary policy, as well as the almost global transition to the gold standard. Bavaria. Ludwig II, 1864-1886. 1 crown 1866, Munich. NGC PF63+CAM. FDC estimate: CHF 20,000. From Auction Numismatica Genevensis 14 (15 and 16 November 2021), Lot 202.

A Groundbreaking Change in the Monetary System

And then came the 19th century. The people gained more power and demanded a currency system that even the simplest farmer would be able to understand. The money of account and the coins actually minted increasingly became one and the same. To make it easier for everyone to use these coins, the value was stamped on them right away, as illustrated by the Bavarian coin shown here: the inscription tells us that, in accordance with a coinage treaty, fifty such crowns were to be minted from one Cologne pound of gold. The monetary system changed rapidly in the late 18th and 19th century. Each nation chose one single currency, whose value was fixed exactly. For example, the American Coinage Act of 1792 states that each dollar must be equivalent to 371 4/16 grains of pure silver. In its 1850 Federal Coinage Act, Switzerland postulated that its new single currency, the franc, should contain 4.5 g of fine silver, following the French franc. The problem here was that it wasn't just silver coins circulating in all these countries, but also gold coins, and the price ratio between gold and silver was constantly changing due to the many new gold and silver mines being discovered in the 19 th century. The prices of precious metals were rising and falling more quickly than many governments were able to respond to them.

Gold From California, Silver From Virginia City

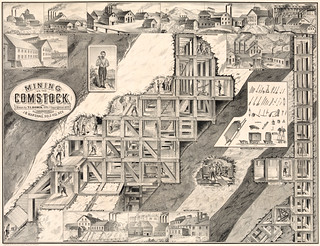

At that time, the price of silver was in free fall because the enormous yields from the Comstock Lode, located in Virginia City, Nevada, caused the world's silver production to skyrocket to 2,544 t between 1861 and 1870. By way of comparison, this figure had been 772 t between 1841 and 1850, before rising to 1,760 t between 1851 and 1860. Between 1901 and 1910, 5,681 t of silver were mined around the world. And of course, this had an impact on the price of silver. Whereas in 1870, the London Fix price for one ounce of silver was 60 pence, it fell to 47 pence in 1890 and then to 28 pence in 1900.

Impact on the Global Economy

Therefore, a large proportion of the 6,000 t of silver contained in the coins that were withdrawn following the change in currency was reminted into German Reichsmarks. Of course, some of it also flowed into the global market. And that was an excellent excuse for all the silver barons in Virginia city, who were furious that their substantial financial investments were no longer paying off due to the dramatic drop in the price of silver on the global market. To put it into specific terms: between 1871 and 1885, the ratio between gold and silver fell from 1:15.51 to 1:32.6! And by the way, the rumour that the monetary reform in Germany was solely responsible for the drop in the price of silver is still perpetuated in many numismatic books to this day.

The Emergence of the Morgan Dollar

A Conference in Paris in 1885

A Broken Master Die and an Issue that was Never Realized

Although a competition was held in 1886 to select the new coin design, it wasn't until 1888 that the design could be used to mint an extensive issue of 5-franc coins. Thus, the rare Swiss 5-franc coin from 1886 is an historic piece that proves that globalisation is not just something that has emerged in the past few decades. The rareness of this coin was caused by the same historical events that led to the prevalence of the American Morgan dollar, which was minted 6,400 kilometres away.

For more information on the sale, see:

Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|