PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

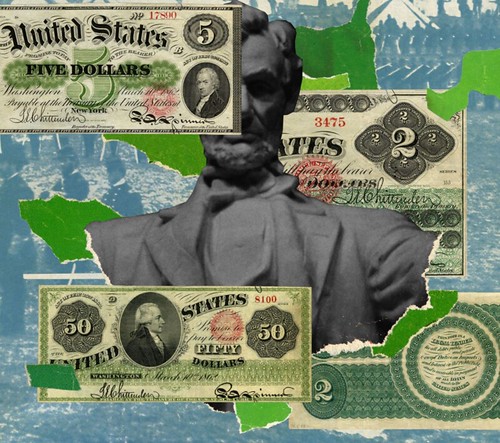

V25 2022 INDEX E-SYLUM ARCHIVE NEW BOOK: WAYS AND MEANSLast week I almost published a Wall Street Journal review of a new book by Roger Lowenstein on the financing of the U.S. Civil War. I decided not to because the review of Ways and Means had nothing to say about the numismatics of the war. But in a new article this week, an excerpt from the book, Lowenstein discusses the creation of Greenbacks - "How Paper Money Saved the Union." Here's an excerpt. -Editor

Spaulding meant for his paper to be

The idea was shocking to his contemporaries. The U.S. had issued Treasury notes, but unlike those, Spaulding's notes would not pay interest and would not have a maturity date. Today, we scarcely think of the fact that the bills in our wallet do not pay interest—after all, they are

The ensuing debate was profound. The Civil War money printers (unlike some central bankers today) agonized over the potential for inflation. They also feared that paper money would jeopardize America's moral standing. William Fessenden of Maine, the powerful chair of the Senate Finance Committee, said the proposal

The heated question before Congress was: Should the new paper circulate voluntarily, or should it be compulsory for all debts and obligations? Chase, who had an inflated sense of his moral authority, told Spaulding he was

However, the cost of the war was approaching $2 million per day (nine times the prewar budget). Soldiers and suppliers were going unpaid. Faced with possible bankruptcy, Chase flipped and demanded

Even with Chase on board—and even as thousands of their sons were being slaughtered—legislators were greatly troubled. Objection came from both parties. Rep. George Pendleton, an Ohio Democrat, said legal tender was a

Support was greater in the West, where money was scarcer and farmers reflexively favored easier credit. One Westerner who supported the bill was President Lincoln, who looked past constitutional qualms to the plain necessity. As he said to the quartermaster general, Montgomery Meigs, Business interests supported the bill, reckoning that the new paper would stimulate commerce. The new money was instantly popular among soldiers, civilians and merchants. To the dismay of Jefferson Davis, greenbacks, as they came to be called, penetrated deep into Dixie, an early warning sign that the Confederacy was in trouble. A bill for Confederate legal tender was introduced in Richmond, but the rebel Congress was disinclined to so expand the powers of the central State. Northern traders initially valued greenbacks at 2% less than the equivalent in gold, a discount that widened (at times drastically) according to the ebb and flow of Union armies. As opponents forecast, Congress returned for a second issue of $150 million in 1862, and a third in 1863. By then, inflation was escalating and the Republicans stopped authorizing more. Wartime inflation totaled 80%, a serious hardship, but never close to the runaway inflation of 9,000% in the Confederacy. The Union's relative success owed much to Congress's decision to enact comprehensive federal taxes rather than, as in the South, relying almost exclusively on the printing press. Legal tender gave the country a trusted currency and kept the government afloat at a dire moment. In his memoirs, Sen. John Sherman called the Legal Tender Act the turning point. After the war, greenbacks were eventually retired, and the nation returned to gold. But the Civil War experience proved to be a foretaste of modern monetary policy. The gold standard was abridged during the Great Depression, and in 1971, President Nixon cut the gold link for good. Since then, the dollar has been fiat money, backed only by faith in the U.S.

To read the complete articles (subscription required), see:

Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|