PREV ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

THE MONEY ART OF VICTOR DUBREUILPablo Hoffman passed along a great article on the money art of Victor Dubreuil. Thank you. Here's an excerpt. -Editor After supposedly stealing 500,000 francs from his bank, the mysterious Victor Dubreuil (b. 1842) turned up penniless in the United States and began to paint dazzling trompe l'oeil images of dollar bills. Once associated with counterfeiting and subject to seizures by the Treasury Department, these artworks are evaluated anew by Dorinda Evans, who considers Dubreuil's unique anti-capitalist visions among the most daring and socially critical of his time. In October 1893, an unidentified reporter for the New York World visited Victor Dubreuil's studio on West Forty-Fourth Street to ask him about his deceptively realistic paintings of United States currency. Several of his pictures had drawn public interest when they were displayed over the bar in a Seventh Avenue saloon. What the journalist found, when the door opened, was a kindly, fifty-one-year-old, virtually penniless Frenchman who spoke heavily accented English and shared his accommodations with a young nephew. As the writer described Dubreuil, the artist had a bent, portly form, dark eyes, and a grizzled black beard. When he went out, he wore a wide-brimmed black hat. This recently recovered journalist's interview reveals an educated man of strong opinions and many talents. And it helps fill a longtime gap in basic knowledge about Dubreuil and his cryptic, socially-critical images.

Born to middle-class parents on November 8, 1842, he was baptized Marie Victor The´odore Dubreuil in the town of Ayron, near Poitiers. On the record, his father is listed as a landowner. From what is known, Dubreuil joined the French army as a soldier in his twenties and fought in the Second Franco-Mexican War as well as the Franco-Prussian War. Then he settled in Paris, working as the director of an exchange bank. On May 29, 1878, at age thirty-five, he married Virginie Lenoir, a widow fifteen years his senior. By the spring of 1881, he had become a socialist agitator and co-founder of a short-lived newspaper called La politique d'action. He also tried to found a norm-breaking African development company. According to his interviewer, the company would

Dubreuil arrived in New York on June 6, 1882, applied for U.S. citizenship, and found short-term employment as a stable boy for the banker The´ophile Keck. In his flight to avoid prison, he left his wife behind and later divorced her. As the journalist reported, after four months of work in the stable, Dubreuil taught himself to paint still lifes, genre scenes, landscapes, and even portraits, so that he became, in his own words,

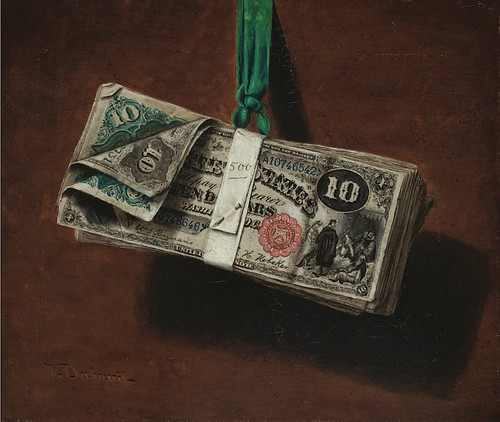

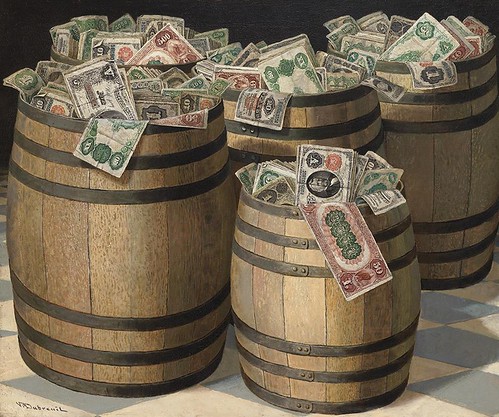

At the time of the New York World interview, Dubreuil was best known for trompe l'oeil images of legal currency, such as Take One. Similar pictures had been produced by some of his American contemporaries, including William Michael Harnett, since at least 1877. As in Harnett's case, the illusionism of Dubreuil's bank notes drew public admiration, which is why he was pursued for an interview. The reporter described two of his larger works on view at the Seventh Avenue saloon in some detail. The first, entitled Barrels O' Money (unlocated), was an unusual depiction of unattainable wealth. It showed rows of oak casks filled with freshly minted treasury bills, topped with

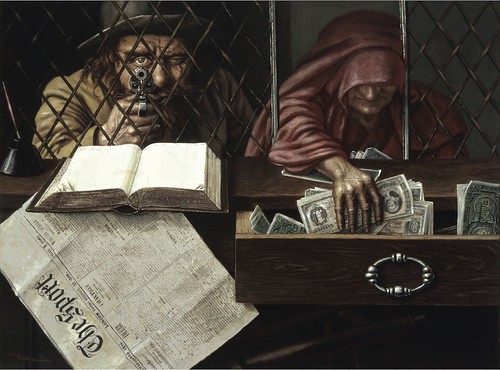

Now called Don't Make a Move!, the canvas, painted during a time of economic depression, is identified in the article as A Prediction For 1900; or, a Warning to Capitalists. This first title and visual evidence within the painting imply that the subject is an allegorical indictment of international banking. The artist himself, shown wearing his signature broad-brimmed hat and pointing a pistol at the viewer, and his

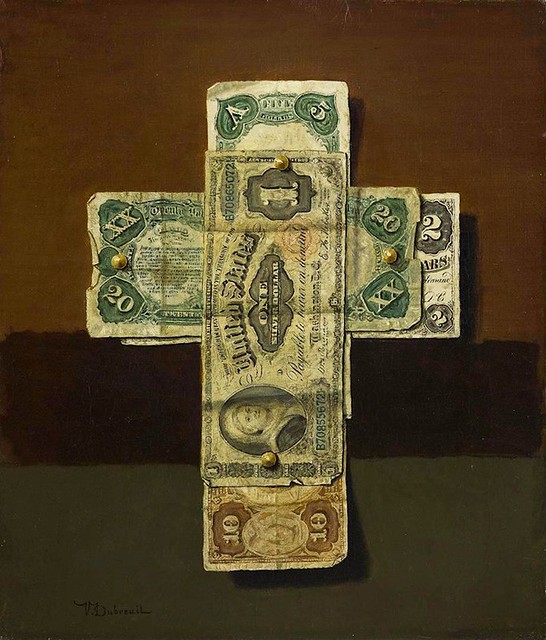

Another money painting, The Cross of Gold, derives its title not from the artist but from a famous speech that the presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan gave in the same decade in which the work was made. Bryan's address (now called

As a painted subject, currency increased in popularity among still-life painters in New York at the end of the century. Compared with his competitors, Dubreuil was less prolific and more uneven an illusionist than most. In fact, some of his bank notes are quite loosely painted and mostly fanciful, as in a second robbery picture, A Hard Day's Work. Yet while his pictures could be cruder or less exact than those of his better-known contemporaries, they were also more strident in content. Alfred Frankenstein, who in 1953 was possibly the first art historian to mention Dubreuil, admired and reproduced Don't Make a Move! as the artist's masterpiece, later noting with approval its See the complete article online for much more. Very interesting! -Editor

To read the complete article, see:

Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|