PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

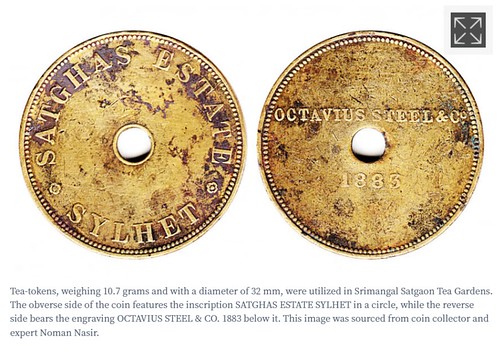

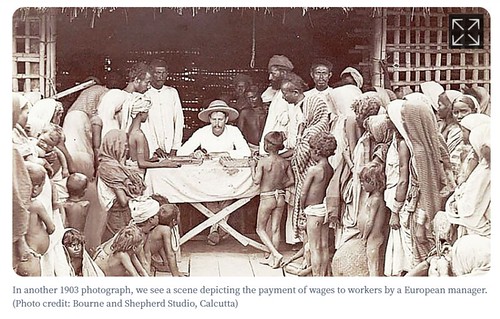

TEA TOKENSHere's an excerpt from a very nice article on tea tokens from The Daily Star. See the complete article online for more. -Editor The emergence of tea as a beverage in India is a unique social event in history. Sylhet, Assam, Cachar, Dooars, and Darjeeling were preferred for tea production, considering the hill climate favorable for tea production. These tea regions were known as Surma, Assam, Barak, and Brahmaputra valleys. Tea production began in the middle of the 19th century. At that time, it was unprofitable for the plantation authorities to pay the wages of the workers in the government currency. That's why workers were given tea-tokens as wages. This facilitated the payment of daily, weekly, or monthly wages to a large group of workers. These not only reduced the hassle of storing large amounts of petty cash but also reduced the financial burden on tea planters. There were tokens of different values, pi, paisa, anna, and then. They were of all shapes and sizes; such as round, oval, triangular, hexagonal, and octagonal. The value of the tokens was fixed in relation to the wage rate of the workers. The use of tokens was limited within the geographical boundaries of the garden. As everyone concerned with the garden was well aware of their value, no problem would have arisen. For almost a hundred years, these tokens have played an important role in the lives of tea workers. Basically, the stories and accounts of the discovery of these tokens are known from the journals related to currency. Why and how the tea-token based system was developed in tea plantations despite the existence of the monetary system in British India is discussed in the article. The "pai" served as the smallest unit of currency used in British India after the monetary system stabilized. Above the "pai" were the "money," then the "anna," and finally the "rupee," with 192 "pies" or 64 paise to one rupee. One anna was equivalent to 12 pies, and 16 annas made up one rupee. To pay the wages of workers, a significant number of small denomination coins such as "pies," "paisas," and "annas" were required. However, due to a shortage of these coins from the mint, the authorities of tea estates faced considerable challenges and had to go to great lengths to mint large quantities of money to obtain the necessary coins. To address this crisis, many tea estate authorities began using tea-tokens as their medium of exchange. These tokens were made from brass, zinc, copper, and tin. In addition to metal tea-tokens, there were traces of colored cardboard eight-anna value tokens (of Assam Company). Some tokens had a face value, while others were based on work rates, such as the Quarter Hazri type tea-tokens. The term "Hazri" used in the tokens originated from "Hazira." "Day attendance" was the method of remuneration in those days, with a specific type of work assigned for "Dayhajira," meant to be completed within one day. There was a fixed rate of daily remuneration for this work. The wage system for tea plantation workers differed from that of other industries or agriculture, as jobs were allocated to families rather than individuals, with husbands, wives, and minor children all contracted to work. "Tikka," or extra work, was compensated at a slightly higher rate. According to coin collector and expert Shankarkumar Bose, several hundred tea-tokens have been identified from a total of 85 tea plantations in Assam, Barak, and Brahmaputra valleys, including 54 in the undivided Surma (Sylhet) valley. These tokens typically measured twenty to thirty-two millimeters in width and predominantly featured English characters. Some tokens also bore inscriptions in Assamese or even Bengali, such as "Chilet." While some tokens had writing on only one side, most had inscriptions on both sides. Notably, none of these tokens displayed denominations; they solely featured the name of the tea garden. Presumably, to avoid the attention of the Labor Inquiry Commission, many tea estates refrained from indicating monetary values on their tokens. Furthermore, many tokens were engraved with the year of issue, and most of them featured round holes in the center. Three different shapes of tokens were used for male, female, and child laborers, with the remuneration rates being highest for adult male workers.

To read the complete article, see:

Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|