PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

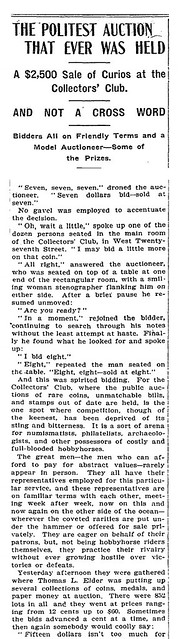

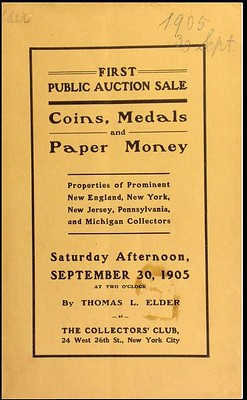

THE POLITEST AUCTION THAT EVER WAS HELDJulia Casey writes: "I found this last night and thought readers might like it. It's an entertaining read from a New York Times reporter who covered the Thomas Elder sale held on September 30, 1905. This article appeared in the October 1, 1905 issue. Attached is my transcription." Thank you! Great find. -Editor

THE POLITEST AUCTION

THAT EVER WAS HELD ______

A $2,500 Sale of Curios at the

AND NOT A CROSS WORD ______

Bidders All on Friendly Terms and a

No gavel was employed to accentuate the decision.

And this was spirited bidding. For the Collector's Club where the public auctions of rare coins, unmatchable bills, and stamps out of date are held, is the one spot where competition, though of the keenest, has been deprived of its sting and bitterness. It is a sort of arena for numismatists, philatelists, archaeologists, and other possessors of costly and full-blooded hobbyhorses. The great men—the men who can afford to pay for abstract values—rarely appear in person. They all have their representatives employed for this particular service, and these representatives are on familiar terms with each other, meeting week after week, now on this and now again on the other side of the ocean—wherever the coveted rarities are put under the hammer or offered for sale privately. They are eager on behalf of their patrons, but not being hobbyhorse riders themselves, they practice their rivalry without ever growing hostile over victories or defeats.

One man represented more than a score of customers, some of whom wanted some

one coin while others were anxious to get anything rare, whether coin or stamp or

bill. All were designated by pseudonyms invented to mask their identity, lest rival

agents discover them and supplant the services of the acting representative. There

was

Half a dozen times the bidders and the auctioneer fell into joking until they lost track of where they were. Then it might happen that they would go back a few numbers and sell them over again to make sure that no one was forgotten.

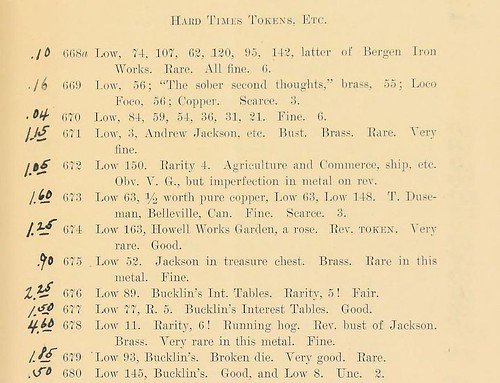

They had got to the section headed

Among the rare pieces that caused the bids to leap upward dollars at a time was a

New Hampshire cent of 1776—a tiny bit of old copper honored in the catalogue

with the epithets A United States silver dollar minted in 1794 brought $62.50, although defective, and the catalogue said that but for its defect it would have been cheap at $175.

In comparison it seemed to the outsider that a good thing was almost given away

when an Egyptian All, in all, the sale realized about $2,500.

To read the complete article, see:

Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|