PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

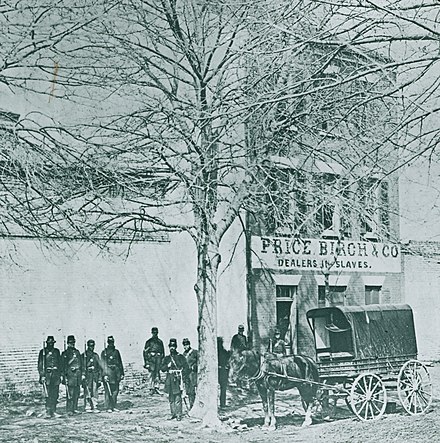

BANKING ON SLAVERYPablo Hoffman writes: "This book excerpt from the Delancey Place blog is a detailed look into 19th Century banking and financing of an unsavory aspect of United States history." Thanks. Here's an excerpt of the excerpt - see the complete book for more: Banking on Slavery: Financing Southern Expansion in the Antebellum United States by Sharon Ann. -Editor "Just as for any other merchant, access to credit was critical for the numerous slave traders who transported hundreds of thousands of surplus enslaved individuals from the states of the old South to the booming cotton and sugar plantations of the frontier. As Allen Gunn of Yanceyville, North Carolina, complained in 1835 to his slave-trading partner Joseph Totten, who was then traveling in Alabama: ‘[E]very man that can get credit in the Bank and his situation will let him leave home is a negro trader.' Yet as far as southern bankers were concerned, slave traders were little different from any other interstate merchant. Traders discounted their own sixty-day promissory notes at a Virginia or North Carolina bank and purchased enslaved individuals with the proceeds. They then transported the people to Mississippi or Louisiana, selling them at a profit-sometimes for cash but often receiving another promissory note as payment, which they discounted at a local bank. With the balance, they repaid their original promissory note and began the cycle anew. As Isaac Franklin of the slave-trading firm Franklin & Armfield advised his Richmond, Virginia, associate Rice Ballard ( of the firm of R. C. Ballard & Co.) in January 1832, ‘should you stand in need of funds you may borrow from your Banks at 60 or ninety [days] with full confidence that the money will be remitted to meet it.' "Yet in an economy without a uniform currency, this interstate trade in remitting money was not quite so straightforward. Banknotes declined in value based both on the reputation of the issuing bank and the distance the banknote traveled from that bank. Mississippi banknotes would be worth far less once they arrived back in Virginia. On one occasion in 1834, an associate of Rice Ballard who was then in charge of preparing ‘40 odd Negroes suitable for shipping' complained that he had tried to cash a check of Ballard's from the Bank of Virginia but ‘they did not want Virginia funds.' One alternative to this interstate movement of funds was for a merchant to obtain a bill of exchange from one bank, payable at another bank with which the bank had a correspondent relationship. For example, several southern banks solicited agreements with the private Girard Bank in Philadelphia during the 1830s. The Girard arranged with the Bank of Louisiana in June 1834 to accept foreign exchange in each other's name for up to $250,000. At the same time, the bank was willing to discount notes arriving in Philadelphia of the Planters' Bank in Natchez for up to $50,000. The Girard Bank reached other correspondent agreements during the 1830s with the Northern Bank of Kentucky, the Mechanics' and Traders' Bank of New Orleans, the Commercial Railroad Bank of Vicksburg, the Union Bank of Mississippi, the Grand Gulf Banking and Railroad Company of Mississippi, and the New Orleans Gas Light and Banking Company. "Once these agreements were in place, banks and their customers could more easily move funds between locations. In April 1832, the Planters' Bank of Mississippi issued a bill of exchange for $7,000 payable ‘at sight' at the Phenix Bank in New York, to the order of R. C. Ballard & Co. Two months later, Ballard received another bill of exchange from the Planters' Bank, payable at the Phenix Bank for $10,000. Presumably, Ballard or one of his associates had discounted $7,000 and then $10,000 in promissory notes with the Planters' Bank—the proceeds of slave sales in Mississippi. Ballard or a representative of his firm could then present each bill at the Phenix Bank to receive New York banknotes. When payments due to the Planters' Bank arrived in New York—perhaps from the sale of cotton in England—these funds would be deposited at the Phenix Bank to the credit of the Planters' Bank, canceling its debt from the bill of exchange.

To read the complete article, see:

Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|