PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

ARTICLE CREDITS OLIVER POLLOCK WITH CREATING DOLLAR SIGN

Quoting Jim Woodrick, the Historic Preservation Division Director of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, a November 23,

2015 article on the blog Atlas Obscura credits businessman Oliver Pollock with creating the dollar sign. The article doesn't

cite other sources, so I'm not sure if Woodrick or the author knew of Eric Newman's work on the topic. Here's an excerpt.

-Editor

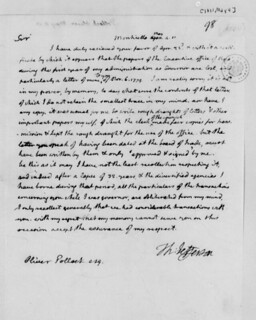

Wars cost money. So when the Revolutionary War broke out, the Colonies turned to a number of sources for backing. The top contributors to America’s Independence: The Kingdoms of France and Spain, the Dutch banking conglomerate, and a single Irish merchant based in New Orleans. His name was Oliver Pollock, and he was the “Financier of the Revolution in the West.” Pollock saw opportunity in war– the chance for a young but wealthy immigrant to stand as a symbol of success and greatness. He desired to carve out a place for himself in America’s financial landscape and perhaps even leave a mark in the nation’s history. He achieved all those things. Just not in the way he expected. America was a British colony in revolt, so the preferred currency became the Spanish dollar, also known as Spanish peso, which was commonly obtained through illicit trade in the Spanish Caribbean. This was the exact manner of trade in which Oliver Pollock made his fortune. Pollock reached into his own deep pockets and made available to the American war cause 300,000 Spanish pesos. That amount is valued at roughly one billion dollars in today’s currency. It was a massive sum, even for someone as wealthy as Pollock, but he gladly parted with it in order to back the revolution. After all, Pollock was Irish, and he believed that fighting Britain was his duty. As important as it was to root for the right horse, Pollock was still a businessman; he believed a sizable investment in the Revolution would pay dividends in the long run–and give him access to some of the most famous names in America. When Pollock reached out to the Founding Fathers to support his new plan, they had no problem backing their man in New Orleans. “Investors were willing to purchase because of the public support given Pollock by Thomas Jefferson, who then served as Governor of Virginia,” explains Light Townsend Cummins in his paper “Oliver Pollock and George Rogers Clarks’ Service of Supply: A Case Study in Financial Disaster.” The “Financial Disaster” part of the aforementioned title gives away what happened next–Oliver Pollock went broke. The expensive cost of raising of armies and supplies left him with nothing. To make matters worse, as a result of some favorable re-negotiating on the bills of exchange he had issued, he was made liable for them, as opposed to the merchant companies and the state congresses who originally backed them. His creditors came looking for repayment. Pollock had no choice but to turn to his Northern friends for help. “Letters from Pollock...were read on the floor of Congress, and the Commercial Committee resolved that the U.S. Treasury should pay Pollock more than twenty thousand dollars…” writes Kathleen DuVal, in Independence Lost: Lives on the Edge of the American Revolution. But neither Congress or the state of Virginia had twenty thousand dollars to spare. Oliver Pollock backed the right horse. It just didn’t pay off. Ironically, said nation-building did include Secretary of Finance Alexander Hamilton’s plan to establish a strong central bank and currency. Washington’s Superintendent of Finance, and Pollock’s close friend and business partner, Robert Morris–himself a key financial backer of the Revolution–began the process by sifting through the countless ledgers sent to Congress by Pollock, who, per Dr. Cummins,“kept careful record of these amounts, noting both the Bills which he received and the supplies which he purchased.”

“Pollock...entered the abbreviation ‘ps’ by the figures for ‘peso.’ Because Pollock recorded these Spanish “dollars” or “pesos” as ‘ps” and because he tended to run both letters together, the resulting symbol resembled a ‘$,’” says Jim Woodrick, the Historic Preservation Division Director of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History. That’s it. Historians have analyzed the source of the $ symbol and have yet to find it written down prior to Pollock’s use in his ledgers. His unintentional creation is supported by the fact that Robert Morris chose to adopt the symbol and by 1797 had it cast in type in Philadelphia as the official symbol for new nation’s own currency. Meanwhile, Oliver Pollock did the only thing he could do. He declared bankruptcy in early 1782 and liquidated his assets and personal possessions. Oliver Pollock is proof that while money can buy many things–from victorious armies to powerful connections–it can’t guarantee what sometimes happens by accident: a legacy. To read the complete article, see:

Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|