PREV ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

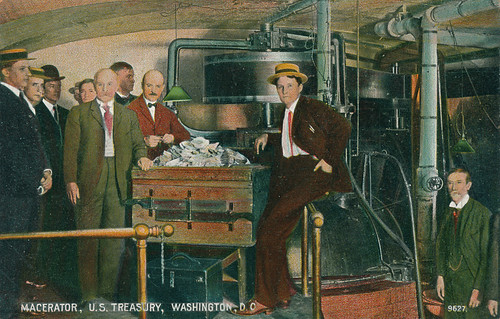

FEATURED WEB PAGE: MACERATED MONEYThis week's Featured Web Page is an article about macerated currency at the Treasury Department.An act of Congress in 1862 authorized the Treasury Department to come up with a method for destroying old paper notes that were no longer fit for circulation. At first they were burned in a special furnace located on the "White Lot" behind the White House, but this method proved to be problematic. It was hard to thoroughly incinerate bundles of notes, and undestroyed fragments could escape through the chimney. Enterprising individuals would scour the White Lot for fragments of bills that they then submitted to the Treasury Department for replacement, claiming the notes had been accidentally burned. Treasury officials soon caught on to the scam, however, and looked for a better way to destroy old bills. In 1874 a new method of destruction was approved: maceration, the shredding of the bills into millions of tiny worthless bits of paper. The curious thing is that this tedious procedure, borne of practical necessity, blossomed into one of Washington's biggest tourist attractions in the late 19th century. Charles M. Pepper, writing in Every-Day Life in Washington in 1900, found the maceration process "one of the most entertaining features of the Treasury Department." Tourists, after seeing how new money is made at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, could visit the Treasury and be taken down to a "sub-cellar room hid away from the face of the earth." There they would witness Treasury employees dumping millions of dollars worth of worn currency into the macerating machine, which dutifully chewed it all into confetti. It was great fun.

www.streetsofwashington.com/2012/10/

All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster |