PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

THE COINAGE OF PERGAMON

While I don't collect ancient coinage, I do enjoy the writing of Mike Markowitz. Here's an excerpt from his July 14, 2016

CoinWeek column on the coinage of Pergamon. Be sure to read the complete version online. -Editor

NOW AND THEN IN HISTORY, economic, political and social forces come together in just the right combination to make a particular city the dynamic locus of cultural creativity. We see this in Athens in the time of Pericles (c. 495 – 429 BCE), Florence during the Renaissance (c. 1350 – 1450 CE), London in the reign of Elizabeth I (1558 – 1603), and Berlin during the Weimar Republic of the 1920s, to give but a few examples. During the Hellenistic era (c. 323 – 30 BCE), Pergamon (or Pergamum[1]) was that kind of place. Art, literature, philosophy and science flourished amid magnificent architecture under the sensible and enlightened rulers of the Attalid dynasty for almost 150 years. Alexander

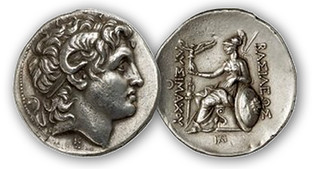

The obverse bears the familiar head of Herakles wearing the skin of the Nemean lion – a design that would appear on coinage in Alexander’s name for the next two centuries. The reverse bears a standing figure of Athena as goddess of war, holding spear and shield. This represents the idol in Pergamon’s temple dedicated to her. The design also appears on later silver diobols inscribed with Pergamon’s name. Philetairos

Years after the assassination of Seleucus (shortly after his victory against Lysimachus in 281 BCE), Philetairos placed an idealized portrait of Seleucus on the city’s coins but inscribed his own name without title on the reverse. When he died in 263 he left his nephew, Eumenes, in charge of a thriving and prosperous state.

Three examples are known of a tetradrachm, issued about 180 BCE, depicting the head of Medusa in a “3/4 facing view” – a

technically-challenging orientation first used by the great coin die engraver Kimon of Syracuse circa 410 BCE

Pergamon under Roman Imperial Rule

To read the complete article, see:

Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|