PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

THE MYSTERIOUS ANCIENT ORIGINS OF THE BOOK

For bibliophiles, here's a BBC article about the origin of the book, suggested by Roger Burdette. Thanks! -Editor

The book is changing. Electronic books, or ebooks, are more portable than their paper counterparts, capable of being carried in their hundreds on a single reader or tablet. Thousands more are just a click away. It can be argued that ebooks are more robust than paper ones: an ebook reader can be stolen or dropped in the bath, but the books on it are stored safely in the cloud, waiting to be downloaded onto a new device. It is not too much to say that books and reading are in the throes of a revolution. The odd thing is that the current angst over the book’s changing face mirrors a strikingly similar episode in history. Two thousand years ago, a new and unorthodox kind of book threatened to overturn the established order, much to the chagrin of the readers of the time.

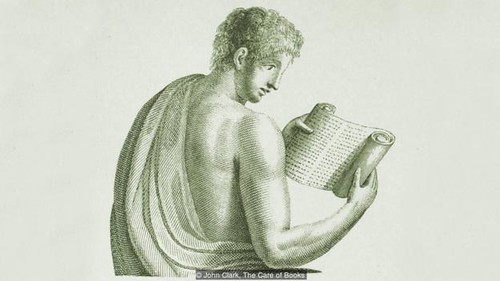

Reading a scroll Scroll with it

The Newfangled Codex Shrouded in mystery

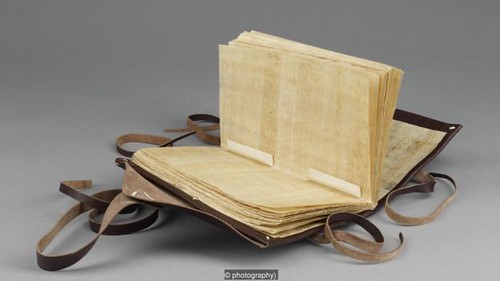

“You who long for my little books to be with you everywhere and want to have companions for a long journey, buy these ones which parchment confines within small pages: give your scroll-cases to the great authors – one hand can hold me.” Written between 84 and 86 CE, Martial’s sales pitch tells us not only that paged books were known of in the First Century CE but also that some of them, at least, were made from a new material called parchment. This alternative to papyrus, invented in a Greek city-state some centuries earlier, was made from cleaned, stretched animal skins by means of a bloody and labour-intensive process, but its smoothness and strength made it an ideal writing material. Archaeologists have since confirmed Martial’s claims via fragments of parchment codices dated to the First Century – and yet, these few tantalising finds aside, we still know very little about where or why the codex was invented, or who might have done so. Whatever the truth of the matter, the paged book was a considerable step forward from the scroll. Codices leant themselves to being bound between covers of wood or ‘pasteboard’ (pasted-together sheets of waste papyrus or parchment), which protected them from careless readers. Their pages were easy to riffle through and, with the addition of page numbers, paved the way for indices and tables of contents. They were space-efficient too, holding more information than papyrus scrolls of a comparable size Yet the people of Rome, and of the lands surrounding it, were split over the merits of the codex. Rome’s pagan majority, along with the Jewish population of the ancient world, preferred the familiar form of the scroll; the empire’s fast-growing Christian congregation, on the other hand, enthusiastically churned out paged books containing Gospels, commentaries and esoteric wisdom. Of course, we know how this story ends: by the Sixth Century, both paganism and the scroll were on the verge of extinction and Judaism had been firmly eclipsed by its younger sibling. Pulled along in the wake of the Christian church, the paged book found its place in history and society. The ebook of the 21st Century may not have as devout a following as the codex of the ancient world, but it inspires strong opinions nonetheless. Will it displace the paper book in its turn, or will it be the one to go the way of the scroll? Time, and booksellers’ profit margins, will tell. To read the complete article, see:

Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|