PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

POLIO PIONEER'S GOLD NOBEL PRIZE MEDAL OFFEREDIn this excerpt from a Sotheby's sale, a gold Nobel Prize medal for a critical discovery regarding polio is discussed. -Editor

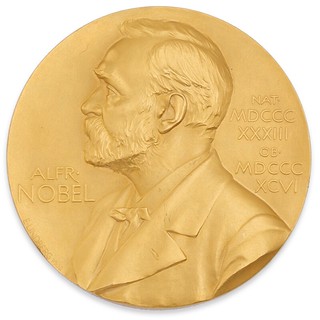

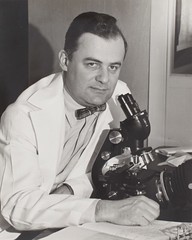

nb: The commissions to execute the Nobel Prize medals were won by two young Scandinavian artists: the “Swedish medals”—Medicine, Physics and Chemistry, and Literature—were entrusted to a twenty-nine-year-old medallist and sculptor, Erik Lindberg from Stockholm, and the “Norwegian medal”—for Peace—to the Oslo-based sculptor Gustav Vigeland (1867–1943). Lindberg (1873–1966) was the son of Adolf Lindberg, a prominent medallist, chief engraver of the Royal Swedish mint, and professor of drawing at the Royal Academy of Fine Art in Stockholm. The younger Lindberg’s career in many ways echoed his father’s. Having studied in Paris where he was influenced by a number of contemporary French masters, most notably Jules-Clément Chaplain, he became a renowned medallist who, in addition to the Nobel medals, designed medals for the 1912 Olympic Games in Stockholm as well as a wealth of other commissions. On his father’s retirement he became the Chief Engraver of the Royal Swedish Mint (1916–1944) and was for decades the Secretary of the Swedish Academy of Fine Arts. Although better known as a medallist than sculptor, a bronze bust of Alfred Nobel by Lindberg was acquired by the National Gallery of Sweden from an auction by Thomas Del Mar in association with Sotheby’s in 2009. Lindberg was working in Paris when he received the Nobel commission in early 1901. Each of the designs for the reverse imagery had to be accepted by the respective institutions responsible for awarding the Prizes and the process of approval by correspondence was slow and at times contentious. Ultimately, Lindberg traveled to Stockholm to personally discuss his concepts. Upon agreement, he prepared plaster models which were reduced in Paris (Lindberg also prepared the dies for the Peace Medal from Gustav Vigeland’s designs). Lindberg’s obverse with the portrait of Nobel, adapted from an anonymous and undated photograph (http://www.nobelprize.org/alfred_nobel/biographical/), was completed before the first presentations of the Prize in 1901. However, the reverses were not yet finished and the initial recipients received base metal examples of the obverse which were replaced by the finished medals in September 1902. Lindberg’s medals were well received, one critic noting that the artist “has shown in the execution of [the medals] a very rare ability, not only in regard to composition and artistic workmanship, but also in the delicacy of expression and feeling of form in his handling of the subjects. His likeness of the donator is excellent” (The Studio, XXVIII, pp. 143–145). The critical reaction to Vigeland’s work was less enthusiastic. Erik Lindberg’s likeness of Alfred Nobel is probably one of the best-known medallic portraits ever created and has become internationally recognized as an icon representing extraordinary achievement. Catalogue Note And yet, as Robbins was to recall more than four decades later, his "involvement with polio came about more or less by accident, and the events leading up to it had little to do with polio" ("Reminiscences of a Virologist," p. 121). Robbins went to medical school at Missouri and Harvard, before training in pediatrics. During World War II he served in the Army in the Mediterranean theater in an epidemiology unit working on a vaccine for typhus and hepatitis. After being discharged from the Army, Robbins returned to Boston Children's Hospital and joined the laboratory recently established by Dr. Enders. The Enders-Robbins-Weller Nobel Prize was to be the only one awarded for research concerning polio. While Joseph Salk and Albert Sabin were nominated for the Nobel Prize, neither was selected. Their contentious public rivalry probably did not advance the cause of either of them. When in 1960, those two were nominated with Hilary Koprowski and Sven Gard in recognition of their polio vaccines, Gard declined the nomination on the grounds that the development of the various vaccines entailed no primary work but simply built on the breakthrough by Enders, Robbins, and Weller. Salk and Sabin did both receive numerous academic and public awards and honors, and Salk supposedly used to remark that he did not need a Nobel Prize because everyone assumed he had one. Frederick Robbins, who did win the Nobel Prize, lived a good and great life, and had, perhaps, the single regret that he did not live to see the global eradication of polio, as he had hoped. I thanked cataloguer David Tripp for including the numismatic details, which are so often overlooked when described in sales outside the numismatic field. -Editor

To read the complete lot description, see:  Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|