PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

THE PROPAGANDA COINS OF THOMAS SPENCEThis article from the site of the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge presents a great overview of the token coinage of Thomas Spence. -Editor

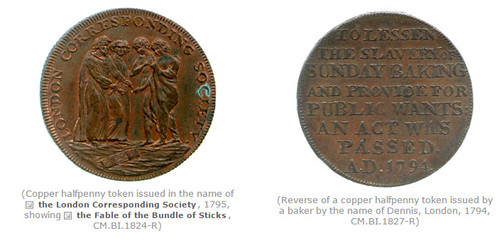

Revolution and Reform on English Tokens Whether for collectors or for commercial use, the possibilities of a freely-circulating medium, almost impossible to police, were obvious to those who wished to spread propaganda against the state, and although the manufacturers and engravers of tokens would happily take commissions from such parties, the issuers could if necessary acquire the necessary machinery to manufacture them alone. Associations of dissenters who felt themselves particular notable, therefore, or those who wished to celebrate one of the few triumphs against the status quo, often had recourse to this form of advertising in copper.  The danger and isolation of dissent led to a grimly humourous camaraderie that makes these tokens witty, but often hard to grasp. The piece below, for example, mimics the commercial issues that invited the buying public to redeem their tokens for silver at the issuer's business address ("Payable at the premises of..."), but the 'address' given by the reverse design is Newgate Jail, because the four men named had been imprisoned there for sedition the previous year.   The joke hangs on the assumption that the prisoners' names would have been known to anyone who happened to receive the token. This is evidence in itself that the doings of revolutionaries were the subject of common report in London. Two of the men named, Henry Symonds and James Ridgway, had been imprisoned for publishing Paine's book. Thomas Spence The obverse of the farthing at left below lists Spence as the first of three Thomases, 'Advocates of the Rights of Man', the others being More and Paine; the reverse at right advertises Spence's penny weekly publication, Pig's Meat, the title of which played upon a reference of Edmund Burke's to 'the swinish multitude'.   From the first Spence was alert to the possibilities of tokens as propaganda, and his earliest issue commemorating the 1775 publication of his Plan appears to have predated the 'token mania' by some years and is consequently extremely rare. Once established in London, however, he found not only a ready market, better than for his bookseller's business, but also a fruitful collaboration with the engraver James, whose readiness to depict Spence's ideas in his animated and vivid style led to a riot of high-impact political imagery which much outpaces Spence's rather turgid prose in the communication of not just his politics but his sense of outrage and rebellion. The result has been a kind of immortality that Spence might not, perhaps have wished, compared to the relative obscurity of his actual writings, but which one of his own catalogues shows that he probably expected: "... some of them on account of device, some for neatness of workmanship, and all on account of their great variety, may, nay will claim the attention of the curious in after-ages."  To read the complete article, see:  Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|