PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

BLACK HISTORY IN NUMISMATICSLen Augsburger writes: John Kraljevich is doing a a fabulous Facebook series on Black History Month, featuring one related numismatic item per day. Here are are few excellent examples. Len and John are thinking of ways to repackage the content as part of the Newman Numismatic Portal. -Editor

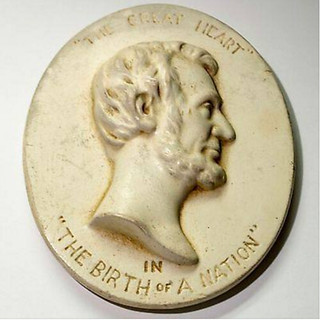

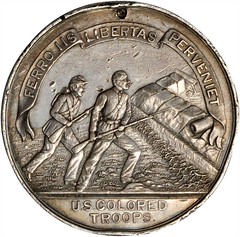

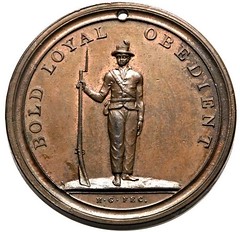

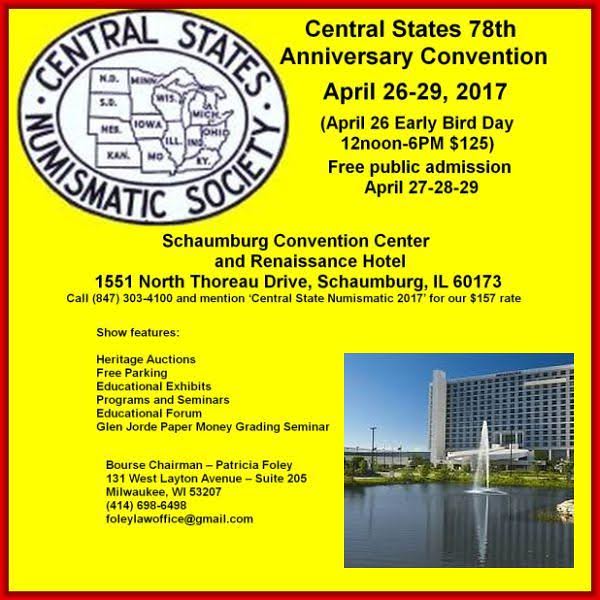

February 1: General Benjamin Butler Colored Troops Medal   In the case of the men who earned this medal in 1864, the fight for freedom was a very literal fight for freedom. As someone who buys and sells historic objects all day every day, it's easy to get jaded. Every once in awhile, something comes along to help you snap out of it. In 1865, Union General Benjamin Butler paid out of his own pocket for a medal to be struck to honor the courage of the men of the U.S. Colored Troops who fought under him on the way to Richmond. "These I gave with my own hand, save where the recipient was in a distant hospital wounded, and by the commander of the colored corps after it was removed from my command, and I record with pride that in that single action there were so many deserving that it called for a presentation of nearly two hundred." 197 medals were struck in silver, most awarded to those who fought. This one actually bears the recipients name on the edge: Abraham Armstead. He was a slave in eastern NC until he got to Union lines and signed up at age 43. Six weeks later, he was the sergeant of his company. Imagine Morgan Freeman in Glory, but real. The medal is inscribed in Latin "Ferro iis libertas perveniet" or "Liberty will be theirs by the sword." Every other one of these I've seen is in nearly perfect condition, laid in a drawer one day in 1865 and forgotten about. It looks like Sergeant Armstead wore this one day in and day out for years. Nobody knows the trouble it's seen. To read the complete post, see: www.facebook.com/john.kraljevich/posts/10212201821740560 February 5: Minstrelry Brooker and Clayton’s Georgia Minstrels are thought to have been the first all-black troupe, founded just after the end of the Civil War. Following their lead, other troupes used the words “Georgia Minstrels” to advertise that their performers were actual African-Americans instead of whites in blackface. This 1877-dated half dollar served as both an advertisement and admission ticket for Sprague and Blodgett’s Georgia Minstrels, which was managed by Charles B. Hicks, the African-American founder of the Brooker and Clayton Georgia Minstrel troupe a decade earlier. According to Matthew Wittman, now the curator of the theatre collection at Harvard’s Houghton Library, “by June 1878 [Blodgett’s] name was dropped from the advertising. The countermarked coins associated with Sprague & Blodgett were thus produced sometime between the fall of 1876 and the spring of 1878.” The illustrated piece is the one in the American Numismatic Society collection. I have a similar one in my own collection, one of perhaps a dozen or two extant. To read the complete post, see: www.facebook.com/john.kraljevich/posts/10212239815810388 February 9: St. Vincent Black Corps   Perhaps the most notable example of pitting the enslaved against Native Americans took place on the West Indian island of Saint Vincent during the Second Carib War of the mid 1790s. The Caribs (for whom the Caribbean was named) were a synthetic tribe formed by the various indigenous peoples who had not died out in the violence and plagues in the decades following Columbus’ arrival. By the 18th century, the Caribs were called “Black Caribs,” a people whose heritage was a mix of the island's indigenous residents and former slaves that either escaped to their communities or were shipwrecked. An uprising of the Caribs in the 1770s was put down by the British military forces on Saint Vincent, but another followed in the 1790s, inspired by the uprising that had created the nation of Haiti. Intent on putting down the second uprising, the British military establishment raised two regiments of men who had been recently enslaved: some were purchased and freed to make them soldiers, some were promised their freedom if they fought. Termed the Saint Vincent Black Corps, these men of African heritage were placed alongside British regulars and local militias to fight against other men of African heritage, the Black Caribs. Those who fought under the British flag were free men thereafter. Those men and their officers were granted a military decoration that depicted a black solder with the three words the British military thought best summarized their new troops: BOLD, LOYAL, OBEDIENT The Black Caribs were defeated and sent in exile to Honduras, where their descendants are today known as the Garifuna, culturally distinct and speaking a language similar to the one Columbus heard when he first landed in the West Indies in 1492. To read the complete post, see: February 10: Birth of A Nation Lincoln Plaque The film was largely inspired by a novel and play called The Clansman, which is a better summation of its plot line than the title given to the screen adaptation. Its storyline adapted the historical events at the end of the Civil War with a grossly fictionalized view of Reconstruction that better fit the Lost Cause ideology then popular than any historical reality. Its caricatures of African-Americans not only dramatized the worst derogatory stereotypes of the era, but made plain that the only way to combat the lustful and thieving nature of the black underclass was with violence. The year Birth of a Nation appeared in theatres, 56 African-Americans were lynched. The film’s racial violence did not go unnoticed or unchallenged in the African-American community, whose fight against it proved a greater legacy than any cinematic artistry the film displayed. Despite the protests, the film became America’s first enormous box office success, packing theatres in big cities and small towns around the country. Its glorification of the Ku Klux Klan is considered the main fuel in the Klan’s re-invention after 1915, causing it to rise to political power throughout the Midwest after being all but dead.Trotter’s protests had succeeded nonetheless, not only in inspiring the power of the African-American community to join in common cause, but in limiting the movie’s spread: a planned 1921 revival was banned in Boston. This small plaque of Lincoln was distributed to those who attended Birth of a Nation’s 400th screening at the Illinois Theatre in Chicago on December 20, 1915. The following spring, the members of the on campus chapter of the Ku Klux Klan at the University of Illinois posed for a group photograph for the first time. To read the complete post, see:  Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|