PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

NEW YORK TIMES REVIEWS IMAGES OF VALUE EXHIBIT

As noted in an earlier article in this issue, The Grolier Club in New York is hosting an exhibit by researcher Mark Tomasko titled "Images of Value: the Artwork Behind US Security Engraving 1830s-1980s." Thanks to Pablo Hoffman of NYC for forwarding a New York Times review of the exhibit, published February 23, 2017. Here's an excerpt from the article headlined "The Secret Art History on Your Money".

-Editor

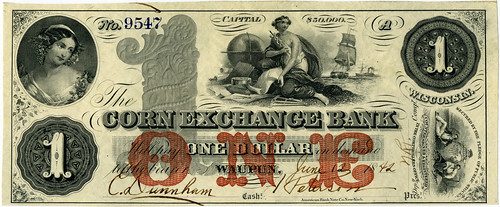

Money talks. And these days, it also walks. American currency is set for its biggest image overhaul in decades as an old face is demoted — that means you, Andrew Jackson! — and some new ones, less uniformly white and male, arrive. The images on legal tender are perhaps the most widely circulated art in the world, but where do they come from? That’s the question explored by “Images of Value,” an exhibition at the Grolier Club in Manhattan devoted to the underpondered truism that financial art, like the bills it is printed on, doesn’t grow on trees. The more than 250 items on view come from the collection of Mark D. Tomasko, a retired lawyer who became fascinated by the beauty of financial art at age 10, when his grandmother gave him an obsolete stock certificate from the old Marmon Motor Car Company. Today he is the rare collector who focuses on tracking down the original artwork behind the engravings on bank notes, stock certificates and other financial documents. “It’s a bit of an Easter egg hunt,” Mr. Tomasko said during a recent interview in the gallery, taking out his smartphone to show a visitor the hundreds of engraved “fancy heads,” or decorative female heads, he keeps on hand for reference. “I enjoy putting together the puzzle.” The show, on view through April 29, presents a kind of shadow art history, driven not by bohemians in their studios or working en plein-air but by a rarefied if staid-looking crew of artists and engravers who suited up every day to work at outfits like the American Bank Note Company. The company was the king of an industry that — like the dollar itself — ruled the world well into the 20th century, when financial “dematerialization” and other forces took their toll. Today, going cashless is easy, but when paper is required Mr. Tomasko likes his lucre very clean. “I only use new money,” he said, pulling a hyper-crisp Benjamin out of his wallet to point out its high-tech anti-counterfeiting features. And what happens when he gets change? He paused, then said, deadpan: “I try not to get change.” Here is a sampling of items Mr. Tomasko has retrieved from the vast, gorgeous and sometimes bewildering dustbin of American financial art history.

So Fancy

Founding Mother The faces on the front weren’t always the all-dude lineup we know today. Before there was Harriet Tubman (coming soon to the $20), there was Martha Washington, who appeared solo on the front of a $1 silver certificate in 1886 (shown above), and then alongside her husband on the back of another one issued in 1896. (Today, George has the $1 all to himself.) The bureau has no record of the source image, but Mr. Tomasko said it was a portrait by Charles François Jalabert, which he also circulated via 19th-century cards, magazine illustrations and lithographs. Like all United States currency issued since 1861, these bills remain valid at their full face value, but if you want to buy an 1886 Martha, you’ll need to fork over as many as 1,500 Georges.

The Master If there’s a true maestro of this art in the show, it’s A. E. Foringer. Foringer, who trained with the muralist Edwin Blashfield, had his 15 minutes of fame with “The Greatest Mother in the World,” a Madonna-like Red Cross poster from 1918 — the only work mentioned in his 1948 obituary in The New York Times, Mr. Tomasko noted a bit forlornly. But Foringer also had a long career as a vignette artist for American Bank Note, creating images that appeared on more than 50 international bills and many stock certificates, including a series for the Canadian Bank of Commerce in the 1910s and 1920s that Mr. Tomasko calls “the most beautiful bank notes of the 20th century.”

To read the complete article, see:

Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|