PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

JOSEPH BREINTNALL'S NATURE PRINTINGJoe Esposito of Springfield, VA forwarded this article from the Philadelphia Inquirer about Ben Franklin, Joseph Breintnall and nature printing on colonial paper money.

Thanks! -Editor

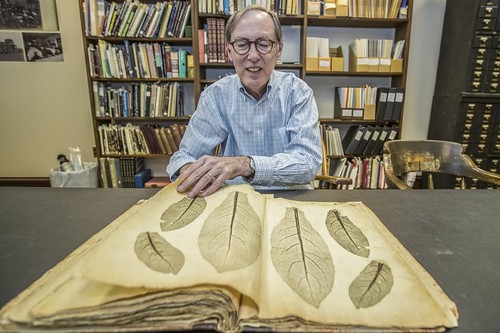

They met in the 1720s, strivers, tradesmen, hungry for skills to improve themselves and Philadelphia. They both loved books and inspired a small group of friends to organize the Library Company of Philadelphia, the first sustainable public lending library, pooling membership dues to order books from England to share and discuss. You know the leader: Benjamin Franklin. His friend Joseph Breintnall, a colonial-era scrivener whose careful handwriting was in demand as America came into being, is one of several remarkable book enthusiasts featured in “The Living Book,” an exhibit now on display at the Library Company. Breintnall‘s largely forgotten life story could fill volumes: friend of Ben, horticultural partner to John Bartram, unlikely midwife to Pennsylvania’s paper money, nature lover obsessed with snakes (and ill-fated snakebite victim), and tragic figure who walked into the Delaware River one day and kept walking until he drowned. In addition to books, Breintnall was crazy about plants. He roamed nearby woods, collecting leaves from trees he could not identify. “He wasn’t so much a botanist,” said Finkel, “as he was fascinated by the sheer beauty.” Because of his elegant penmanship and writing skills, Breintnall became secretary of the Library Company. It was his duty to order books from their London agent, Peter Collinson. Even better, Collinson was a member of the Royal Academy. Finally, someone to help identify the trees Breintnall so dearly loved. Trouble was, by the time ships crossed the ocean, leaves crumbled. Breintnall had to find a better way. Inspired by Franklin, Breintnall slathered both sides of freshly picked leaves with thick, indelible printer’s ink and sandwiched them between two sheets of paper. He made impressions using a heavy roller. It took a long time for the oil-based ink to dry, but the resulting prints — one of which is featured in “The Living Book” — were startling in their beauty and detail. “They were far more accurate than anything produced by copperplate engraving, a technology not yet available in the colonies,” said Library Company librarian Jim Green. Breintnall sent these prints to Collinson, who shared them with fellow academics and British horticulturalists. Not only did the experts identify the plants; they also bought the prints. “Franklin wanted to win the contract to print Pennsylvania’s currency,” Green said. “Counterfeiting was a serious issue. To create designs too unique to fake, he and Breintnall made plaster molds of leaves resting on fabric. They used these molds to make lead printing blocks.” Innovation won Franklin the lucrative contract. “Very few of the banknotes that Franklin printed personally still exist,” Green said. “But here is currency printed with his molds.”  Franklin’s objective was profit. Breintnall’s was the pursuit of natural science and authenticity. “He was an imaginative and disturbed man,” Green said. His widow, Esther Parker, donated two volumes of leaf prints made by her husband to the Library Company. In gratitude for Breintnall’s dedicated service, the Library Company voted her a gift of 15 pounds and, for their son, free lifetime use of the books. To read the complete article, see: Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|