PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

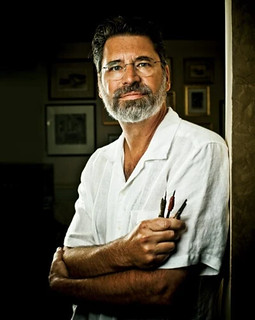

THOMAS HIPSCHEN: FACE VALUEWhile looking for other things (*cough* Gene Hessler) I came across this great 2010 Washingtonian article about BEP portrait engraver Tom Hipschen. -Editor

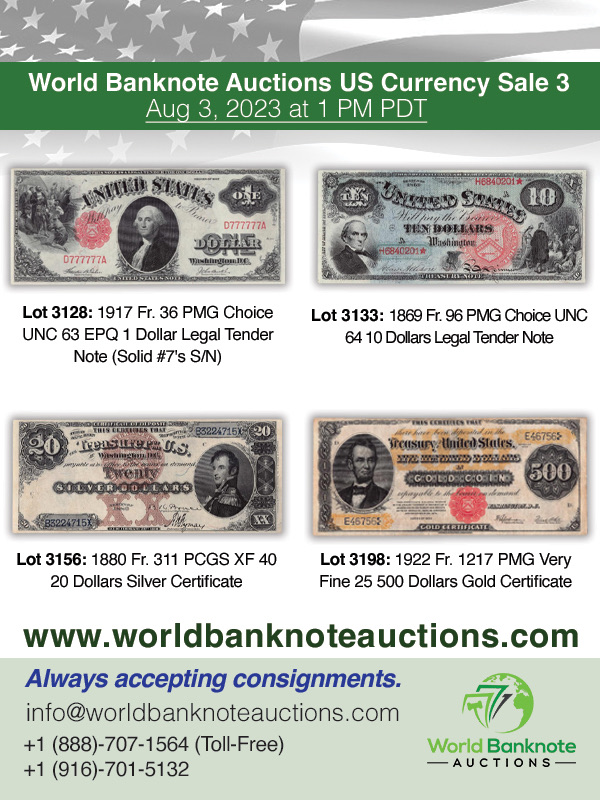

Hipschen is considered one of the world's best portrait engravers. But when the Treasury Department rolls out a new $100 bill in February, the engraving on the front—a fuller portrait of Franklin—will be Hipschen's last. The two-centuries-old tradition of hand engraving is fading away. Bank-note artists who cut tiny dots, dashes, and lines into steel plates are putting down their tools and instead using a keyboard and a digital tablet to create images that can be produced in three weeks rather than three months.

But at the same time that the bureau is phasing out hand engraving, it's adding anti-counterfeiting technology. The new $100 bill will have features such as a three-dimensional ribbon as well as ink that contains microscopic flakes that shift color with movement. Says Stephen Mihm, a University of Georgia professor who specializes in the history of money: A magnifying glass held to Benjamin Franklin's coat—which Hipschen lengthened for the new $100 bill—and to the facial and eye area on the left side of the note, reveals lines that are alternatively heavy, thin, dark, and light. Slanted, tic-tac-toe-like crosshatches with dots inside create depth and texture.

Hipschen has spent decades studying engravings—especially those from the 1920s and '30s—to learn ways to use open space, lines, and dots.

Hipschen's interest in art was sparked at age eight, when he saw a drawing of a young hare by the German Renaissance engraver Albrecht Dürer in a magazine. Hipschen dreamed of studying art in college but knew that with ten children in the family (he was second-oldest), his parents couldn't afford it. A door to art opened when his cousin Bob Jones, a postage-stamp designer at the Bureau of Engraving in DC, returned home to Iowa to visit and saw Hipschen's work. Jones knew the bureau was searching for an apprentice and encouraged his cousin to apply.

Hipschen traveled alone to Washington at age 17 with a bus ticket his grandfather had bought. He sketched a still life, competing with dozens of older artists before winning the post. He credits his youth with helping him get the job: Hipschen started as an apprentice in 1968, peeling tiny threads of steel off a plate with a pointed chisel, called a burin, to create a seven-cent stamp of Ben Franklin, who designed the country's first paper money—continental dollars issued to pay for the American Revolution. Franklin used plaster casts of leaves to create lead plates and then print images of the leaves on dollars, because each leaf was unique and therefore hard to counterfeit. As an apprentice, Hipschen received permission from the bureau to moonlight for the Canadian government to engrave portraits on $10 and $50 bank notes of John A. Macdonald and William Lyon MacKenzie King, the first and tenth prime ministers. The precision of his work attracted attention among currency experts around the world. He was approached by countries on three continents to engrave their currency, and he received proposals to create illegal engravings. When one man asked Hipschen to copy travelers' checks, he gave the information to the Secret Service.

Despite his skill, Hipschen's work long remained anonymous.

There's much more to this great article, so be sure to read the full version online and learn about Hipschen's years "crouched over an angled, lighted table

To read the complete article, see:

Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|