PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

MIKE DIAMOND INTERVIEW, PART TWOHere's the second part of Greg Bennick's CONECA interview with collector and writer Mike Diamond, covering Mike's approach to learning about the minting process. Thanks again to Greg, ErrorScope Editor Allan Anderson, and CONECA for making this available here. -Editor Mike Diamond: Oh yes. Greg Bennick: So, this is how you learned the minting process, through Arnie's work and Alan Herbert's work. And I'm assuming that when you mention James Wiles, you meant that he had an ANA course?

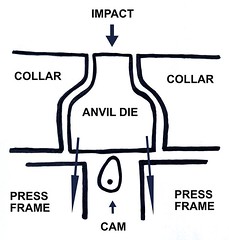

Greg Bennick: You mean in Arnie's book, in terms of the cam? Mike Diamond: Yes, it made a whole lot more sense once I got an explanation. I couldn't imagine a cam withstanding the tons of pressure. Greg Bennick: How do you recommend people today learn the minting process, given that Arnie's book, for example, is somewhat dated at this point, even if many of the basics are still accurate? How do you recommend people learn the minting process now? Mike Diamond: Yeah, that's tough because all the references are out of print. It's unfortunate. I tried to get some numismatic publishers interested in a book. I wrote a few sample chapters, and submitted photos, along with a table of contents. But they ultimately all rejected it. They didn't think there was enough of a market for it. Greg Bennick: That's too bad. I'm actually a little bit surprised. I would think that there would be quite a market, potentially, for it. Mike Diamond: Well, I went to Whitman Press, I forget which other presses I went to, but they all turned down the idea. And I didn't feel like pursuing a vanity project. Greg Bennick: That makes sense. Now, I see you as a scientist of error coins in a way. I tend to appreciate the esthetics of errors but when I read your articles and your columns and whatnot, it is as if you're a scientist who also appreciates the esthetics. The science part is fascinating because it shows a level of study and research that's beyond the norm. I was wondering if you might talk about your discoveries, the ones this scientific approach has led you to, because I know you've made an incredible number of discoveries over the years. Mike Diamond: Well, as you say, I approach each error with an analytical bent. I like to know exactly what happened. Sometimes I can't establish exactly what happened. There are still a number of errors in my collection I know that are genuine (laughs) but I don't know how they came to be. But, you know, my background is in science. I approach things in a scientific fashion. I use my knowledge of the minting process to establish limits of what could have happened. Looking at the features of the coin, I'm able to deduce, and to reconstruct in many cases, more or less what happened. I'm able to think three dimensionally. I credit that in part to my training in anatomy, which compelled me to see the human body in three dimensions, as I would dissect each cadaver to show its contents to the students I was teaching. I visualize the moving parts involved: the hammer die, the anvil die, the collar, the feeder / ejector. You try to visualize exactly how they fit into the picture, and how they might be responsible for the physical appearance of the coin. Greg Bennick: And this is why the minting process and knowledge of it, whether a rudimentary knowledge from older books or as close to current knowledge as one can get, is so essential. Because without that baseline knowledge of the minting process, a visualization is going to fall flat. Mike Diamond: There was a recent article in Coin World on illicitly applied die impressions. Personnel in the back room were monkeying around with planchets and coins, applying dies - either real or crudely fabricated - to planchets and coins, creating what seem to be, and what are, bizarre looking specimens. The one I had was a proof nickel, where the first strike was a genuine -- either an in-collar uniface strike or struck by an early-stage uniface die cap. And after that they monkeyed with it, applying a non-proof nickel obverse die to the featureless obverse face and impressing a second design that looks die-struck but actually isn't struck in a press. Some of the proofs go for thousands and thousands of dollars because those are hard to fake. No one's going to take a proof error, which is highly valuable, and screw around with it outside the mint. Now the business strikes, they just look like crude attempts at creating a counterfeit. Greg Bennick: It seems as though proof errors were not nearly as prevalent in terms of their availability years ago. Now all of these proof errors from the early seventies, San Francisco dated, are all over the place. Every auction seems to have them. What do you think about that? Mike Diamond: Yeah, I've noticed that. I guess people have been sitting on them for decades and figure that now's the time to sell. And naturally, the vast majority were created on purpose, and, some of them represent illicitly applied die impressions. There's a proof Eisenhower dollar planchet with a weakly impressed Jefferson proof obverse design. And then if I recall correctly, a brockage from a proof dime on the reverse. The planchet was sandwiched between a Jefferson proof die and a dime proof coin. And I'm not exactly sure whether they used a mallet or some other device to press the images. But like almost all these illicit impressions, it's very weakly struck. It sold for big bucks.

Greg Bennick: I'm sure it did. I'm sure it's because they're curiosities, if nothing else. But I'm just intrigued by that because one of the things that I learned early on from some of the, so-called old timers, as it were, Arnie and whatnot, was that, there were Mike Diamond: Right. It's my understanding that all of these errors, of larger coins struck with smaller designs, were intentionally created. Because it is hard to imagine how the larger disc would fit into the chute that deposits the coin into the feeder, and how it would fit into the feeder/ejector, which has very tight tolerances. There was a recent column of mine where I, as best I could, took measurements of the spacing between the two feeder fingers of a quarter feeder and the quarter itself. And there was basically no room for anything larger than a quarter planchet. Greg Bennick: So that speaks to the idea that a quarter planchet would literally have to physically be placed by hand, essentially placed directly between the dies for that cent strike to occur. Mike Diamond: Yes exactly. There are periods where these strikes on oversized discs are more common, like 1981 and 2000. In Canada, 1978 was the big year where you see cent designs struck on all manner of larger planchets and coins. A number of errors formerly considered impossible are now well documented, like major misalignments of the anvil die. All the resources I read said there was no possibility. And yet such coins are well documented. Greg Bennick: Do you think that mint employees see the minting process differently than we do. Meaning we have picked up the pieces as best we can and we've figured out the minting process as well as research and history have allowed. But do you think Mint employees would tell a very different tale than what we tell about errors and the process that creates them?

Mike Diamond: Quite possibly. But reversing that, some mint employees know less than we do. Like Sean Moffitt, he was the fellow I was talking about earlier, who worked in lots of private mints. I had a long e-mail exchange with him years ago where I worked to convince him that stutter strikes are real and that they exist. He first insisted though, that this was impossible. I kept showing him one example after another and he finally caved and said,

More of Greg's error interviews can be found in previous issues of Errorscope magazine.

For more information on the Combined Organization of Error Collectors of America (CONECA), see:

To read the earlier E-Sylum article, see:

Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|